Long before digital databases and cloud storage, ancient civilizations developed sophisticated systems to catalog and preserve humanity’s collective knowledge, laying foundations we still use today.

📜 The Dawn of Information Organization in Ancient Mesopotamia

The story of cataloging begins in the fertile valleys of Mesopotamia, where Sumerian scribes faced a challenge remarkably similar to modern information professionals: how to organize vast amounts of data for easy retrieval. Around 3200 BCE, these early librarians created clay tablet catalogs that listed temple inventories, legal documents, and literary works with impressive precision.

The Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh, dating to the 7th century BCE, represents perhaps the most sophisticated ancient cataloging system discovered. Archaeologists unearthed over 30,000 clay tablets, many bearing what we would recognize today as metadata—including titles, first lines, number of tablets in a series, and even colophons identifying scribes and dates of copying.

These Mesopotamian catalogers understood a fundamental principle that remains vital today: consistency in classification enables efficient retrieval. They organized materials by subject matter, including divination, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, and literature, creating discrete collections that anticipated modern library sections.

🏛️ Egyptian Papyrus Collections and the House of Life

Ancient Egypt’s approach to information management centered around institutions called “Houses of Life,” attached to major temples. These weren’t merely storage facilities but dynamic centers of learning where priests cataloged religious texts, medical treatises, magical spells, and administrative records.

Egyptian catalogers developed hierarchical classification systems based on content type and purpose. Religious texts received priority placement, followed by royal decrees, then practical manuals for various professions. They created inventory lists on papyrus scrolls, noting the physical condition of documents, storage locations, and circulation status for borrowed materials.

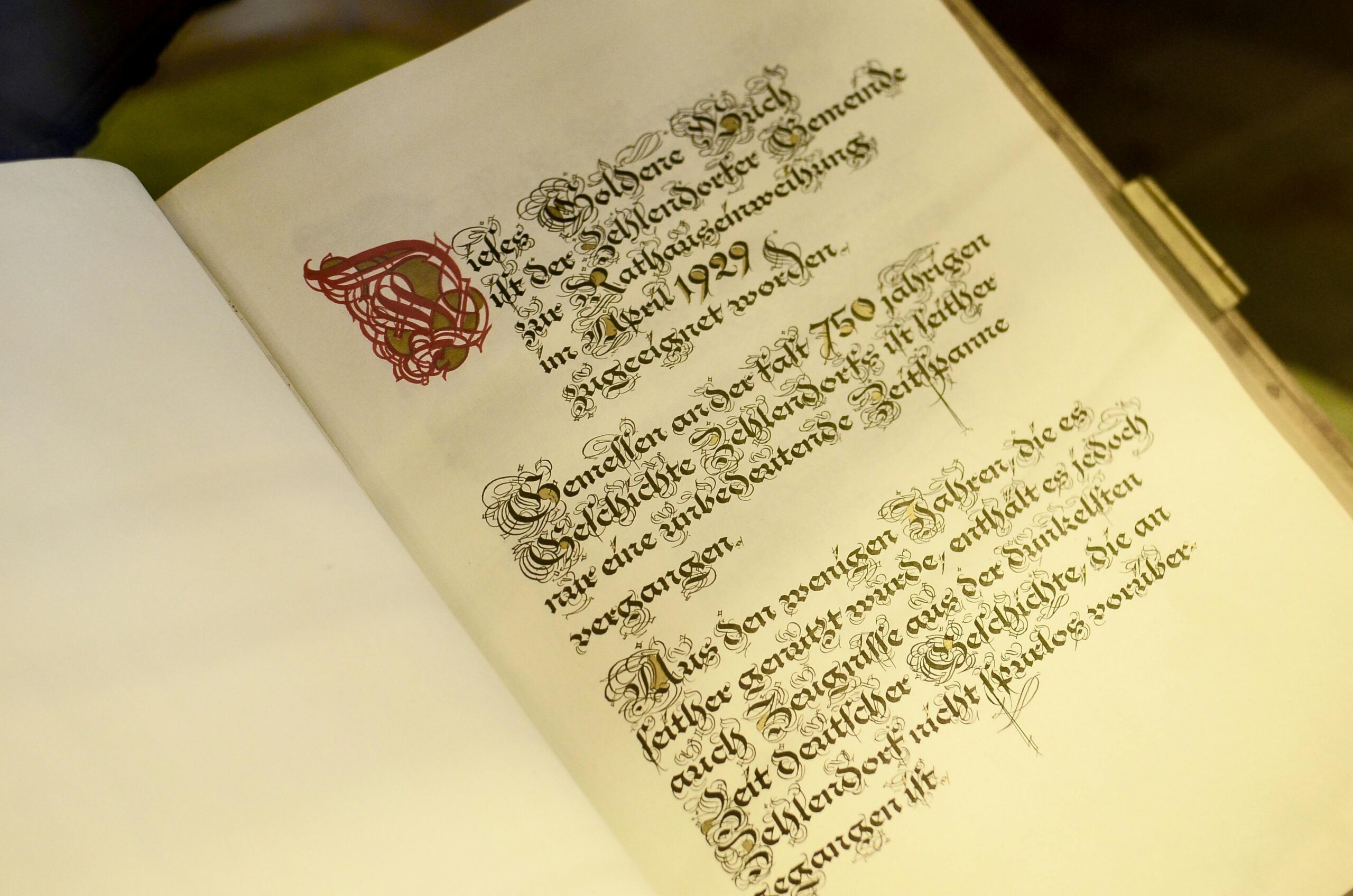

The practice of labeling storage containers with content descriptions—essentially external metadata—emerged during this period. Pottery jars and wooden boxes housing papyrus scrolls bore inscriptions detailing their contents, making retrieval possible without opening every container. This technique directly parallels modern folder naming conventions and file tagging systems.

Preservation Through Duplication

Egyptian scribes understood that information preservation required redundancy. Important documents were copied multiple times, with each copy stored in different locations. This distributed storage approach protected knowledge from localized disasters—a concept echoed in modern backup strategies and cloud storage distribution.

📚 The Revolutionary System of Alexandria’s Great Library

The Library of Alexandria, founded around 300 BCE, represented the pinnacle of ancient information management. Its chief librarian, Callimachus, created the Pinakes—a 120-volume catalog that listed approximately 500,000 scrolls and became the ancient world’s most comprehensive bibliographic reference tool.

Callimachus organized the Pinakes into broad categories: rhetoric, law, epic poetry, tragedy, comedy, lyric poetry, history, medicine, mathematics, natural science, and miscellaneous writings. Within each category, authors appeared alphabetically, with biographical information, lists of their works, and even critical annotations about authenticity and textual variants.

This system introduced several innovations still fundamental to modern cataloging:

- Standardized author entries with biographical context

- Alphabetical arrangement within classifications

- Cross-referencing between related works

- Documentation of textual variants and editions

- Attribution verification and authenticity notes

- Physical descriptions including scroll length

The Pinakes essentially functioned as an ancient union catalog, aggregating information about holdings across multiple collections. This networked approach to cataloging anticipated modern library consortia and shared catalog systems by over two millennia.

🎭 Roman Pragmatism in Information Architecture

Roman contributions to cataloging emphasized practical accessibility over theoretical elegance. Roman libraries typically organized works by language (Greek versus Latin), then by genre, reflecting the bilingual nature of educated Roman society.

The Romans pioneered physical innovations that improved information retrieval. They developed the codex format—bound pages rather than scrolls—which allowed for easier page-turning and more compact storage. Codices could include internal tables of contents and page references, features impossible with scroll formats.

Roman administrators also created extensive archival systems for government records, establishing document retention schedules that specified how long different record types should be preserved. Tax records, census data, military reports, and legal proceedings each had designated storage periods—establishing principles of records management that remain relevant today.

The Importance of Findability

Roman librarians attached tags (tituli) to scroll rods, visible when scrolls were shelved horizontally in honeycomb-style compartments called armaria. These tags functioned like modern spine labels, enabling visual scanning without handling individual items. This user-centered design principle—making information findable at a glance—remains central to modern UX design and information architecture.

🕉️ Eastern Approaches: Buddhist and Confucian Cataloging Traditions

While Mediterranean civilizations developed their cataloging systems, Eastern cultures created parallel traditions with distinct characteristics. Chinese catalogers working with bamboo and silk documents during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) developed classification schemes based on Confucian philosophy, organizing texts into four main divisions: Classics, Histories, Masters, and Collections.

This Four-Part Classification system, formalized by the 7th century CE, influenced Chinese bibliography for over a thousand years. Its philosophical foundation—organizing knowledge according to its role in cultivating moral character and good governance—differed markedly from Western subject-based approaches, yet achieved similar goals of systematic organization and retrieval.

Buddhist monasteries across Asia developed sophisticated cataloging practices for their vast sutra collections. The Chinese Buddhist Canon (Tripitaka) required elaborate organizational systems to manage thousands of texts translated from Sanskrit. Catalogers created detailed bibliographies noting translators, translation dates, textual lineages, and commentarial traditions.

⚙️ Timeless Principles Discovered in Ancient Systems

Examining ancient cataloging practices reveals principles that transcend technological change. These foundational concepts remain applicable whether organizing clay tablets, printed books, or digital files.

Consistent Terminology and Controlled Vocabularies

Ancient catalogers recognized that effective retrieval depends on consistent terminology. They developed controlled vocabularies—standardized terms for describing similar items—long before modern library science formalized this practice. When Mesopotamian scribes consistently labeled astronomical texts with specific genre markers, they created a controlled vocabulary that enabled reliable searching.

Modern knowledge organization systems, from Library of Congress Subject Headings to enterprise taxonomy management, directly descend from this ancient insight: consistency in naming enables findability.

Hierarchical Classification With Flexible Subcategories

Ancient systems balanced broad top-level categories with flexible subdivision capabilities. The Pinakes’ major divisions could accommodate new subcategories as knowledge expanded, while Chinese Four-Part Classification allowed for detailed subdivisions within major classes. This hierarchical-yet-flexible approach mirrors modern faceted classification and tag-based organization systems.

Metadata as Separate From Content

Ancient catalogers understood that descriptive information about an item—its metadata—should exist independently from the item itself. Creating separate catalog records, inventory lists, and finding aids meant users could locate information without physically handling every document. This separation of metadata from content underlies all modern database design and content management systems.

🔍 Rediscovering Ancient Techniques for Modern Challenges

Contemporary information professionals face challenges analogous to those confronting ancient librarians: exponential information growth, format proliferation, preservation concerns, and access management. Ancient solutions offer surprisingly relevant insights for digital-age problems.

Distributed Collections and Federated Search

Ancient library networks, like those connecting Hellenistic libraries across the Mediterranean, required coordination mechanisms for sharing catalog information. Modern federated search systems and discovery layers that aggregate metadata from multiple repositories echo these ancient networked approaches.

Version Control and Textual Variants

Ancient scholars meticulously documented textual variants and edition differences, essentially practicing version control. The Alexandrian grammarians’ critical editions, noting variant readings from different manuscript traditions, established practices directly comparable to modern version control systems like Git, which track changes across document iterations.

Access Management and Circulation Systems

Ancient libraries implemented lending policies, maintained borrower records, and tracked item circulation. Egyptian temple libraries recorded when scribes borrowed texts, for what purpose, and expected return dates. These circulation systems established patterns still fundamental to modern library management and digital rights management.

💡 Practical Applications for Contemporary Information Organization

Understanding ancient cataloging principles offers practical guidance for modern organizational challenges, whether managing corporate knowledge bases, personal digital libraries, or community information resources.

Start With Core Categories, Then Refine

Ancient catalogers typically began with broad, fundamental divisions reflecting their worldview’s essential knowledge categories. Modern organizers can apply this approach by identifying 5-10 core categories reflecting their domain’s fundamental divisions, then developing subcategories organically as needs emerge.

Prioritize Findability Over Perfect Classification

Ancient systems favored practical retrieval over theoretical elegance. Roman tituli on scroll rods prioritized visual scanning efficiency over comprehensive bibliographic detail. Similarly, modern systems should optimize for user findability patterns rather than abstract organizational perfection.

Document Your Classification Logic

Ancient catalogers created reference guides explaining their organizational systems, like the introductory volumes of the Pinakes. Modern information architects should similarly document classification rationales, ensuring system maintainability when original creators depart.

Plan for Format Migration

Ancient libraries regularly copied deteriorating scrolls onto fresh media, understanding that preservation requires periodic format migration. Digital information requires similar vigilance—planning for file format obsolescence, storage media degradation, and platform transitions.

🌟 The Enduring Wisdom of Ancient Information Stewards

Ancient catalogers were more than mere record-keepers; they were information architects who understood that organizing knowledge determines its accessibility and survival. Their sophisticated systems emerged from deep engagement with fundamental questions about knowledge organization, questions that remain central to information science today.

The clay tablets of Ashurbanipal’s library, though separated from us by millennia, speak a language modern information professionals recognize: the language of metadata, classification, and retrieval optimization. The papyrus catalogs of Egyptian Houses of Life demonstrate concerns identical to those driving modern digital asset management: version control, access management, and preservation planning.

These ancient systems succeeded because they were built on human-centered principles: understanding user needs, prioritizing practical retrieval, maintaining consistency, and adapting to changing requirements. Technology changes, but these fundamental principles remain constant.

🔮 From Clay to Cloud: Continuing the Ancient Tradition

Today’s information professionals continue work begun thousands of years ago in Mesopotamian temple libraries and Egyptian scribal schools. The tools have evolved from clay styluses to database queries, but the essential mission remains unchanged: organizing humanity’s knowledge so it can be found, used, and preserved for future generations.

The most sophisticated modern information systems—from Google’s search algorithms to enterprise knowledge management platforms—ultimately rest on principles first articulated by ancient catalogers: consistent terminology, hierarchical classification, metadata separation, and user-centered design. Understanding this lineage enriches our appreciation for both ancient achievements and modern innovations.

As we face contemporary challenges like information overload, digital preservation, and knowledge discovery in massive datasets, ancient cataloging systems offer more than historical curiosity. They provide proven principles, battle-tested across millennia, for organizing information effectively regardless of format or technology.

The scribes who carefully labeled clay tablets in ancient Nineveh, the librarians who compiled the Pinakes in Alexandria, and the Buddhist scholars who cataloged vast sutra collections were all engaged in the same essential work that occupies today’s information professionals. Their insights remain timeless because they addressed fundamental human needs: preserving knowledge, enabling discovery, and connecting people with information that matters to them.

By unearthing and understanding these ancient cataloging secrets, we don’t merely honor the past—we equip ourselves with time-tested principles for navigating the information challenges of the present and future. The wisdom of ancient information stewards continues to illuminate our path forward in the digital age.

Toni Santos is a knowledge-systems researcher and global-history writer exploring how ancient libraries, cross-cultural learning and lost civilisations inform our understanding of wisdom and heritage. Through his investigations into archival structures, intellectual traditions and heritage preservation, Toni examines how the architecture of knowledge shapes societies, eras and human futures. Passionate about memory, culture and transmission, Toni focuses on how ideas are stored, shared and sustained — and how we might protect the legacy of human insight. His work highlights the intersection of education, history and preservation — guiding readers toward a deeper relationship with the knowledge that survives across time and borders. Blending archival science, anthropology and philosophy, Toni writes about the journey of knowledge — helping readers realise that what we inherit is not only what we know, but how we came to know it. His work is a tribute to: The libraries, archives and scholars that preserved human insight across centuries The cross-cultural flow of ideas that formed civilisations and worldviews The vision of knowledge as living, shared and enduring Whether you are a historian, educator or curious steward of ideas, Toni Santos invites you to explore the continuum of human wisdom — one archive, one idea, one legacy at a time.