Scribes were far more than simple record-keepers in ancient civilizations—they were the gatekeepers of knowledge, power, and cultural continuity across millennia.

📜 The Sacred Guardians of Written Knowledge

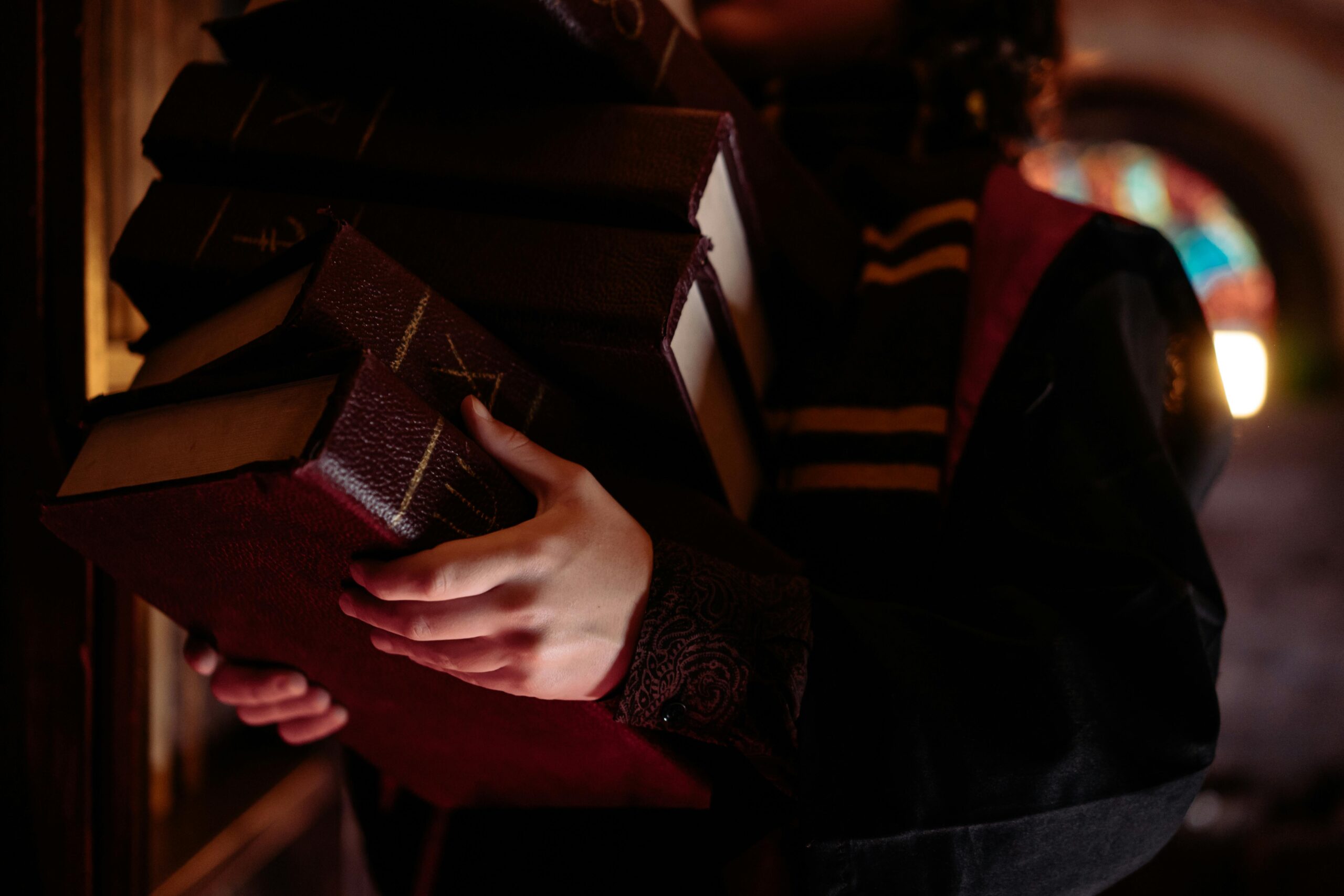

In the dust-covered corridors of ancient temples and palaces, scribes occupied a unique position that transcended mere literacy. These professionals wielded instruments of power more formidable than swords: reed pens, papyrus, clay tablets, and the precious ability to transform spoken language into permanent written form. Their role in shaping intellectual hierarchies cannot be overstated, as they effectively controlled the flow of information in societies where literacy rates rarely exceeded five percent of the population.

The scribal profession emerged alongside the earliest writing systems in Mesopotamia and Egypt around 3200 BCE. As civilizations grew more complex, requiring sophisticated administrative systems, legal frameworks, and religious documentation, scribes became indispensable. They were the architects of bureaucracy, the preservers of sacred texts, and the educators of future generations.

🏛️ Educational Pathways: Creating an Intellectual Elite

Becoming a scribe required years of rigorous training that began in childhood. In ancient Egypt, scribal schools known as “Houses of Life” attached to temples provided comprehensive education. Students spent countless hours copying classical texts, mastering hieroglyphic, hieratic, and later demotic scripts. The curriculum extended beyond writing to encompass mathematics, astronomy, medicine, law, and religious literature.

Mesopotamian scribal education followed similar patterns in the “edubba” or tablet houses. Young students, predominantly from wealthy or priestly families, practiced on clay tablets, copying Sumerian literary classics, mathematical problems, and legal formulas. The investment required—both in time and resources—meant that scribal education served as a powerful mechanism for maintaining social stratification.

The Scribal Curriculum Across Civilizations

Different ancient societies developed distinct educational emphases reflecting their cultural priorities:

- Egyptian scribes mastered multiple script systems and specialized in administrative, religious, or literary domains

- Mesopotamian scribes learned Sumerian as a classical language alongside Akkadian, similar to Latin in medieval Europe

- Chinese scribes devoted years to mastering thousands of characters and classical texts that formed the basis of civil service examinations

- Mayan scribes combined artistic skill with linguistic knowledge, creating elaborate codices and monumental inscriptions

- Hebrew scribes developed meticulous copying techniques to preserve religious texts with extraordinary accuracy

⚖️ Scribes and Social Mobility: A Complicated Relationship

The scribal profession presented one of the few avenues for social advancement in otherwise rigid hierarchical societies. Ancient Egyptian literature frequently praised the scribal calling as superior to manual labor. The “Satire of the Trades,” a popular instructional text, catalogued the hardships of various professions while extolling the comfortable life of scribes who worked with their minds rather than their backs.

However, this potential for mobility had significant limitations. Entry into scribal schools required family connections, financial resources, or patronage from wealthy sponsors. While exceptional talent occasionally opened doors for individuals from modest backgrounds, the profession largely reproduced existing class structures rather than challenging them.

The Economics of Literacy

Scribal services commanded substantial fees, creating economic barriers that reinforced intellectual hierarchies. Illiterate individuals required scribal mediation for legal contracts, correspondence, petitions to authorities, and commercial transactions. This dependency created power imbalances that scribes could exploit, though professional ethics and legal regulations attempted to prevent abuses.

The economic value of scribal skills varied by specialization. Administrative scribes working in palace or temple bureaucracies received regular salaries and rations. Independent scribes operating in marketplaces charged fees based on document complexity. The most prestigious scribes—those serving as royal advisors, temple librarians, or court historians—enjoyed wealth, status, and influence comparable to high-ranking officials.

🔮 Religious Authority and Scribal Power

In many ancient civilizations, scribes held profound religious significance beyond their practical functions. Egyptian scribes invoked Thoth, the ibis-headed god of wisdom and writing, as their patron deity. The very act of writing was considered sacred, capable of bringing words into material reality and ensuring their perpetuation into eternity.

Mesopotamian scribes similarly venerated Nabu, god of writing and wisdom, son of Marduk. Scribal colophons—the signature statements at the end of tablets—often included prayers and invocations seeking divine protection for both the text and its copier. This religious dimension elevated scribes above secular craftspeople, positioning them as intermediaries between divine knowledge and human understanding.

Preserving Sacred Texts and Ritual Knowledge

Priestly scribes controlled access to religious texts, ritual instructions, and esoteric knowledge. In Egypt, the “lector priests” (khery-heb) read sacred texts during temple ceremonies and funeral rites. Their ability to pronounce divine names and magical formulas correctly was believed essential for rituals to succeed. This specialized knowledge created an exclusive domain where religious and scribal authority merged.

Similarly, Jewish scribes (soferim) developed elaborate rules governing Torah production. Every letter required precise formation, specific spacing, and verification by qualified experts. Errors necessitated ritual correction or complete scroll retirement. These stringent standards ensured textual accuracy while reinforcing scribal authority as guardians of divine revelation.

📊 Administrative Functions: The Backbone of Complex Societies

Ancient states depended on scribal bureaucracies to function. Tax collection, resource distribution, legal proceedings, military organization, and diplomatic correspondence all required literate professionals. Scribes created the documentary infrastructure that transformed loose tribal confederations into sophisticated territorial states.

| Civilization | Primary Administrative Focus | Key Scribal Innovations |

|---|---|---|

| Mesopotamia | Tax records, trade contracts | Cuneiform, cylinder seals, standardized legal formulas |

| Egypt | Agricultural monitoring, construction projects | Hieratic script for rapid writing, ostraca for temporary records |

| China | Civil service administration | Bamboo and silk writing surfaces, standardized characters |

| Rome | Legal documentation, military logistics | Cursive scripts, wax tablets, professional notarii |

Scribal Specializations and Career Paths

As administrative needs diversified, scribal specializations multiplied. Some focused on mathematical calculations for taxation and engineering projects. Others specialized in legal formulas, diplomatic correspondence, or historical chronicles. Medical scribes compiled pharmacological knowledge and case studies. Military scribes maintained troop rosters and supply inventories.

This specialization created hierarchies within the scribal profession itself. Chief scribes supervised document production and authentication. Royal scribes enjoyed direct access to rulers and influenced policy decisions. Archive scribes maintained institutional memory by organizing and preserving documents. Each specialization required distinct training and offered different career trajectories.

✍️ Literary Production and Cultural Transmission

Beyond administrative duties, scribes served as authors, editors, and transmitters of cultural heritage. Epic poetry, wisdom literature, medical treatises, astronomical observations, and historical annals all passed through scribal hands. In this capacity, scribes shaped collective memory and cultural identity.

Mesopotamian scribes preserved the Epic of Gilgamesh across centuries, copying and sometimes revising the text for new audiences. Egyptian scribes compiled medical papyri synthesizing diagnostic procedures and treatments. Chinese scribes created standardized versions of Confucian classics that defined educational standards for millennia. Without scribal dedication to copying and preservation, these foundational texts would have vanished.

The Scribal Voice: Authorship and Authority

Some scribes transcended their role as mere copyists to become recognized authors. Enheduanna, daughter of Sargon of Akkad, served as high priestess and composed hymns that bear her name—the earliest known author in history. Egyptian scribes like Ptahhotep and Amenemope created wisdom instructions that became classics. These individuals leveraged scribal skills to achieve literary immortality.

However, authorship in the modern sense remained rare. Most scribes worked anonymously, their individual contributions absorbed into collective traditions. Even when named, scribes often presented their work as revelation from divine sources or transmission of ancient wisdom rather than original composition. This humility paradoxically enhanced their authority by positioning them as faithful preservers rather than innovative creators.

🌍 Scribal Networks: Information Exchange Across Borders

Ancient scribes formed professional networks that transcended political boundaries. International diplomacy required scribes fluent in multiple languages and writing systems. The Amarna letters—diplomatic correspondence between Egyptian pharaohs and Near Eastern rulers—demonstrate how scribes facilitated communication across vast distances using Akkadian as a lingua franca.

These networks enabled knowledge transfer between civilizations. Greek scribes studying in Egypt absorbed Egyptian mathematical and astronomical knowledge. Indian scribes adapted writing systems from Aramaic prototypes. Chinese scribal techniques influenced Korean and Japanese writing development. Through these connections, scribes functioned as cultural mediators, adapting foreign knowledge for local contexts.

⚔️ Power Struggles: Scribes in Political Conflicts

Control over writing meant control over truth claims, legal precedents, and historical narratives. Rulers understood this power and sought loyal scribes who would document their reigns favorably. Scribal families sometimes accumulated multi-generational influence by monopolizing key administrative positions.

Political upheavals often targeted scribal classes. Conquerors might replace existing scribal bureaucracies with their own loyalists, though practical necessity usually ensured continuity. The specialist knowledge scribes possessed made them simultaneously valuable and potentially dangerous—they could expose discrepancies, forge documents, or preserve inconvenient records.

Scribal Resistance and Subversion

While typically portrayed as servants of established authority, scribes occasionally exercised subtle resistance. Deliberate copying errors, unflattering portrayals in historical accounts, or preservation of alternative traditions could undermine official narratives. The power to determine what survived in written form gave scribes significant influence over collective memory, even when they lacked direct political authority.

🔍 Gender Dimensions: Women in Scribal Professions

Scribal professions remained predominantly male in most ancient civilizations, reflecting broader gender hierarchies. However, exceptions existed, particularly in religious contexts. Enheduanna’s literary achievements demonstrate that elite women could access scribal education in Mesopotamia. Egyptian evidence suggests some women served as scribes, though far less commonly than men.

Women’s exclusion from most scribal training reinforced their subordinate social positions by denying them access to literacy and its associated opportunities. This gender barrier in education perpetuated intellectual hierarchies that extended beyond ancient times, shaping literacy patterns for millennia.

📉 The Decline of Traditional Scribal Culture

The introduction of alphabetic writing systems simplified literacy acquisition, potentially democratizing written communication. Greek and Phoenician alphabets required mastering fewer than thirty characters rather than hundreds or thousands of signs. This accessibility gradually eroded scribal monopolies on literacy.

The invention of printing technologies millennia later delivered the final blow to traditional scribal culture. Mechanical reproduction eliminated the need for hand-copying, drastically reducing costs and expanding access to written materials. The scribal profession transformed, with its educational and religious functions persisting while its monopoly on text production disappeared.

💭 Enduring Legacies: Scribal Influence on Modern Intellectual Life

Contemporary intellectual hierarchies retain traces of ancient scribal culture. Academic credentialing systems echo scribal apprenticeships. Scholarly publishing preserves gatekeeping functions once performed by scribes controlling text reproduction. Professional jargon and specialized knowledge domains create modern equivalents of scribal exclusivity.

The reverence for written texts, the authority attributed to documentation, and the prestige associated with literacy all reflect cultural values shaped by millennia of scribal influence. Understanding how scribes navigated and constructed intellectual hierarchies in ancient civilizations illuminates persistent patterns in how societies organize, validate, and transmit knowledge.

The scribal legacy reminds us that literacy has never been merely a technical skill but always a form of social power. Those who control writing systems, educational access, and textual interpretation wield influence disproportionate to their numbers. As we navigate digital information landscapes, the ancient scribes’ experiences offer valuable perspectives on the relationship between knowledge, technology, and social hierarchy—challenges remarkably similar to those faced by societies transitioning to new forms of communication and information storage today.

Toni Santos is a knowledge-systems researcher and global-history writer exploring how ancient libraries, cross-cultural learning and lost civilisations inform our understanding of wisdom and heritage. Through his investigations into archival structures, intellectual traditions and heritage preservation, Toni examines how the architecture of knowledge shapes societies, eras and human futures. Passionate about memory, culture and transmission, Toni focuses on how ideas are stored, shared and sustained — and how we might protect the legacy of human insight. His work highlights the intersection of education, history and preservation — guiding readers toward a deeper relationship with the knowledge that survives across time and borders. Blending archival science, anthropology and philosophy, Toni writes about the journey of knowledge — helping readers realise that what we inherit is not only what we know, but how we came to know it. His work is a tribute to: The libraries, archives and scholars that preserved human insight across centuries The cross-cultural flow of ideas that formed civilisations and worldviews The vision of knowledge as living, shared and enduring Whether you are a historian, educator or curious steward of ideas, Toni Santos invites you to explore the continuum of human wisdom — one archive, one idea, one legacy at a time.