In our interconnected world, knowledge flows across borders at unprecedented speed, raising complex questions about how we ethically share, adapt, and apply information across diverse cultural landscapes.

🌍 The Shifting Landscape of Global Knowledge Exchange

The digital revolution has transformed how information travels between cultures, communities, and continents. What once took months or years to disseminate now happens in seconds, creating both extraordinary opportunities and profound ethical challenges. As researchers, educators, businesses, and individuals navigate this landscape, understanding the cultural dimensions of knowledge ethics becomes not just important—it’s essential.

Knowledge ethics across borders encompasses far more than simple translation. It involves recognizing that different cultures hold fundamentally different perspectives on what knowledge is, who owns it, how it should be shared, and what responsibilities come with its transmission. From indigenous wisdom traditions to cutting-edge scientific research, the ethical considerations multiply when information crosses cultural boundaries.

Understanding Cultural Frameworks for Knowledge

Every culture develops its own framework for understanding and valuing knowledge. Western academic traditions often emphasize individual authorship, empirical verification, and open publication. In contrast, many indigenous cultures view knowledge as communal property, inseparable from spiritual practices and oral traditions. Asian philosophical traditions may prioritize collective harmony and hierarchical transmission of wisdom.

These differences aren’t merely academic—they have real-world implications. When pharmaceutical companies seek traditional medicinal knowledge, when tech platforms aggregate user data globally, or when educational materials are adapted for different markets, cultural knowledge frameworks collide. Navigating these collisions ethically requires genuine cultural competency, not just legal compliance.

The Ownership Question: Who Controls Knowledge?

Perhaps no issue in cross-cultural knowledge ethics generates more debate than ownership. Western intellectual property systems emphasize individual or corporate ownership with time-limited protections. This model struggles when applied to knowledge that communities have maintained collectively for generations.

Traditional knowledge holders worldwide have watched their cultural heritage—from medicinal plants to agricultural techniques to artistic expressions—be documented, patented, and commercialized without consent or compensation. The ethics of this extraction have sparked international movements for indigenous rights and calls for new frameworks that respect collective ownership models.

🔍 Digital Technology and Cross-Border Knowledge Flow

Technology platforms have become the primary conduits for knowledge exchange across cultures, yet they often embed particular cultural values in their design. Social media algorithms, search engines, and content recommendation systems reflect the priorities and biases of their creators, typically based in Western countries.

This technological mediation shapes what knowledge circulates globally and how it’s interpreted. Information architecture decisions—like whether user-generated content defaults to public or private, how content is moderated, or which languages receive algorithmic priority—carry ethical weight when operating across cultural contexts.

Data Colonialism and Information Asymmetry

Critics have coined the term “data colonialism” to describe how information flows from the Global South to tech companies in the Global North, which then profit from insights derived from that data. This pattern mirrors historical colonial extraction of physical resources, but with knowledge as the commodity.

The ethical challenge intensifies because communities providing data often lack the technological infrastructure to analyze it themselves or to meaningfully consent to its use. This information asymmetry creates power imbalances that replicate older patterns of exploitation under new digital guises.

Research Ethics in Multicultural Contexts

Academic and scientific research across borders presents particularly complex ethical terrain. Researchers must navigate institutional review boards, funding requirements, publication pressures, and career advancement while respecting the cultural contexts of research participants and collaborators.

Historical abuses—from medical experimentation to anthropological exploitation—cast long shadows. Building truly ethical international research collaborations requires moving beyond extractive models where knowledge flows one direction, toward genuine partnerships where communities participate in research design, implementation, and benefit sharing.

Key Principles for Ethical Cross-Cultural Research

- Community engagement: Involve communities from project conception, not just data collection

- Benefit sharing: Ensure research outcomes serve participant communities, not just academic careers

- Cultural protocols: Respect local customs around knowledge sharing and sacred information

- Capacity building: Support local research infrastructure rather than extracting data for external analysis

- Long-term relationships: Maintain connections beyond single projects to build trust and accountability

- Language accessibility: Make findings available in local languages, not only English publications

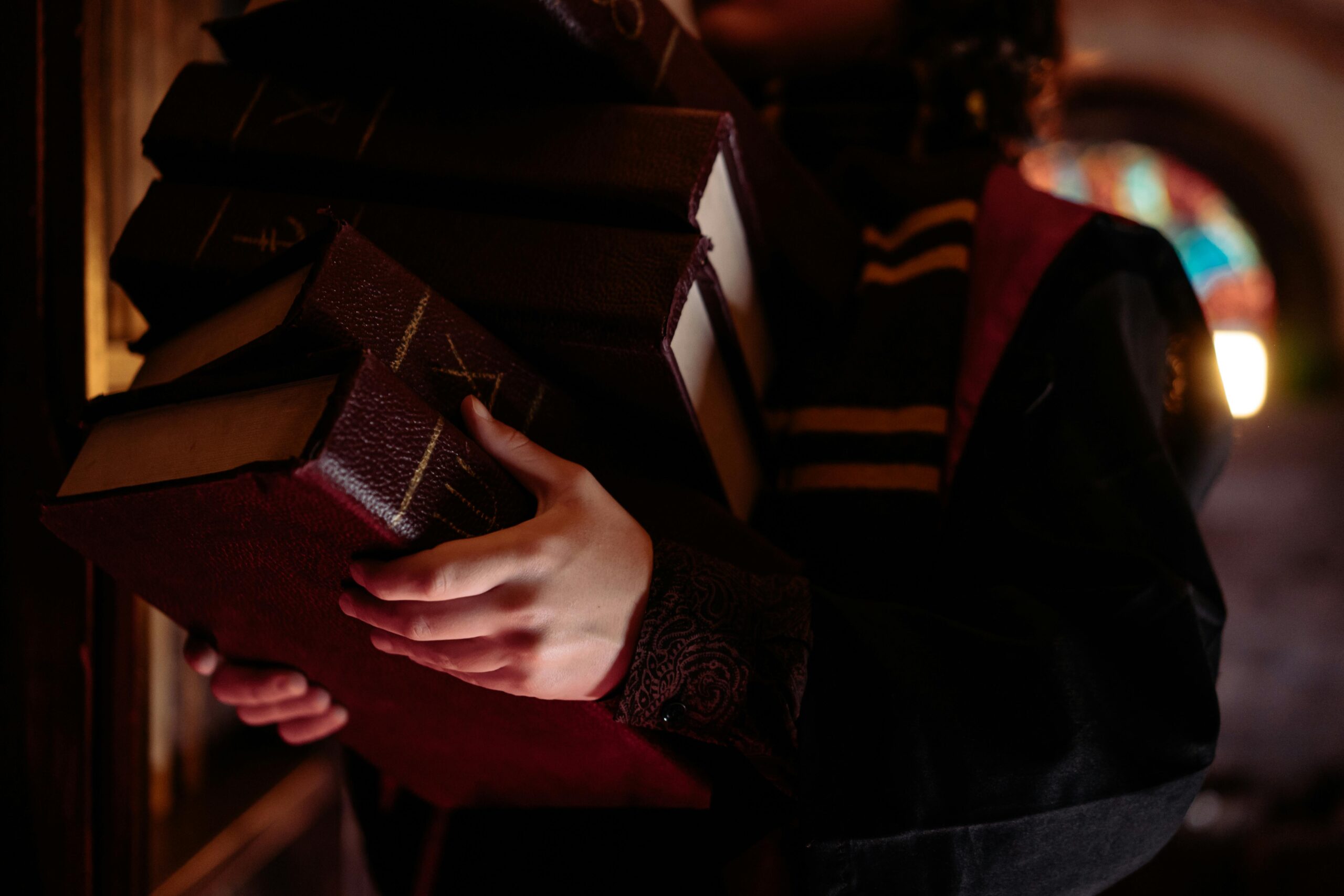

📚 Education and Cultural Knowledge Transfer

Educational systems serve as primary mechanisms for knowledge transmission within and across cultures. As education globalizes—through international schools, online learning platforms, student mobility, and standardized testing—questions about whose knowledge gets taught and how become increasingly urgent.

Western educational models have achieved near-hegemonic status globally, often displacing local knowledge systems. While universal literacy and numeracy provide valuable tools, this standardization can marginalize indigenous languages, traditional ecological knowledge, and culturally-specific ways of learning.

Decolonizing Knowledge in Educational Settings

Movements to decolonize curricula challenge the assumption that Western knowledge is universal while other traditions are merely “local” or “cultural.” This work involves critically examining which voices are centered in syllabi, whose perspectives are treated as authoritative, and how knowledge from different traditions is valued and integrated.

Ethically navigating educational knowledge transfer means creating space for multiple epistemologies—different ways of knowing—rather than simply adding “diverse content” to fundamentally unchanged frameworks. It requires educators to develop cultural humility and recognize the limits of their own knowledge traditions.

Business and Professional Knowledge Ethics

Corporations operating across borders face knowledge ethics questions daily. From protecting proprietary information while complying with varying national regulations, to adapting products and services for different cultural markets, to managing diverse workforces with different professional expectations—knowledge ethics permeates international business.

Many ethical failures stem from imposing home-country assumptions onto different contexts. What constitutes acceptable advertising, appropriate workplace behavior, or responsible data handling varies significantly across cultures. Ethical navigation requires genuine cultural learning, not just legal compliance or surface-level sensitivity training.

Cross-Cultural Professional Communication

Professional knowledge sharing across cultures involves navigating different communication styles, decision-making processes, and relationship expectations. Direct versus indirect communication, individual versus collective responsibility, and varying attitudes toward hierarchy all shape how knowledge is effectively and ethically shared in professional contexts.

Technology companies, in particular, face scrutiny about whether their products and platforms respect cultural differences or impose Silicon Valley values globally. Content moderation policies, privacy defaults, and user interface design all embed cultural assumptions about knowledge, relationships, and appropriate behavior.

🌿 Traditional and Indigenous Knowledge Systems

Indigenous and traditional knowledge systems represent millennia of accumulated wisdom about ecology, medicine, social organization, and spiritual practice. These knowledge systems operate according to different principles than Western academic knowledge, often emphasizing oral transmission, ceremonial contexts, and restrictions on who may access certain information.

Ethical engagement with traditional knowledge requires recognizing its validity on its own terms, not just as raw material for Western scientific validation. It means respecting protocols around sacred knowledge, understanding collective ownership models, and supporting communities’ right to control how their knowledge is shared and used.

Free Informed Prior Consent

The principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) has emerged as an international standard for engagement with indigenous communities. FPIC requires that communities have the right to give or withhold consent to projects affecting their territories or cultural heritage, including knowledge documentation or research projects.

Implementing FPIC ethically means providing information in accessible formats and languages, allowing adequate time for community decision-making processes, and genuinely respecting refusals. It represents a shift from extractive relationships to ones based on respect and partnership.

Legal Frameworks and Their Limitations

International legal frameworks attempt to govern cross-border knowledge flows through intellectual property treaties, data protection regulations, and research ethics guidelines. However, these frameworks reflect particular cultural assumptions and often struggle to accommodate diverse knowledge traditions.

The World Intellectual Property Organization, UNESCO, and various international bodies have developed guidelines for traditional knowledge protection, but implementation remains uneven. Many indigenous communities and developing nations argue that existing systems inadequately protect their interests and perpetuate knowledge extraction.

Emerging Models for Knowledge Governance

New governance models are emerging that attempt to bridge different cultural frameworks. Traditional knowledge databases with customized access controls, benefit-sharing agreements that direct research profits to source communities, and collaborative research frameworks represent evolving approaches to more ethical knowledge exchange.

Some indigenous communities have developed their own protocols for researchers and institutions wishing to work with their knowledge. These protocols assert community authority and establish expectations for ethical engagement, shifting power dynamics in knowledge relationships.

💡 Practical Strategies for Ethical Navigation

For individuals and organizations working across cultural boundaries, developing practical strategies for ethical knowledge navigation is essential. This requires ongoing learning, cultural humility, and willingness to adapt approaches based on feedback and reflection.

Building Cultural Competency

Cultural competency begins with recognizing one’s own cultural positioning and how it shapes assumptions about knowledge. It involves studying the histories, values, and knowledge systems of cultures you engage with, while understanding that competency is an ongoing process, never fully achieved.

Effective cultural learning requires multiple sources—books and academic resources, certainly, but also direct relationships with community members, participation in cultural events when appropriate, and learning from mistakes with humility rather than defensiveness.

Creating Ethical Frameworks for Your Context

Every professional context requires tailored ethical frameworks for cross-cultural knowledge work. Educational institutions need different protocols than businesses, researchers face different challenges than journalists, and each specific project may require unique considerations.

Developing these frameworks should involve diverse perspectives, particularly voices from communities whose knowledge may be affected. Ethics shouldn’t be determined solely by those with institutional power, but through inclusive dialogue that centers marginalized perspectives.

🔮 Future Horizons in Knowledge Ethics

As artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and other emerging technologies transform how knowledge is created, shared, and experienced, cross-cultural ethics questions will only intensify. AI systems trained predominantly on Western data risk encoding cultural biases at unprecedented scale, while also offering potential for preserving endangered languages and knowledge systems.

The climate crisis adds urgency to ethical knowledge exchange, particularly regarding traditional ecological knowledge that may offer insights for sustainability. However, this urgency cannot justify extractive approaches—ethical climate action requires respecting indigenous rights and knowledge sovereignty.

Cultivating Wisdom Across Boundaries

Navigating knowledge ethics across borders ultimately requires moving beyond rule-following to cultivating practical wisdom—the ability to perceive what specific situations require and act accordingly. This involves developing ethical sensitivity, deepening cultural understanding, and maintaining commitment to justice even when it’s uncomfortable or costly.

The goal isn’t achieving perfect ethical clarity—cultural contexts are too complex and ever-changing for simple formulas. Rather, it’s developing the capacity for ongoing ethical reflection, genuine relationship-building across difference, and willingness to prioritize justice over convenience in knowledge relationships.

As our world grows more interconnected, the stakes of these choices increase. How we navigate knowledge ethics across cultures will shape whether globalization amplifies historical injustices or creates new possibilities for mutual learning and flourishing. The compass we need isn’t a fixed set of rules, but a commitment to ethical engagement that respects human dignity and cultural diversity in all their complexity.

Each of us participates in cross-cultural knowledge exchange, whether through our consumption of media, professional work, educational pursuits, or digital interactions. By approaching these exchanges with intention, humility, and commitment to justice, we contribute to building a more ethical global knowledge commons—one that honors diverse ways of knowing and ensures benefits flow to all communities, not just the already powerful.

Toni Santos is a knowledge-systems researcher and global-history writer exploring how ancient libraries, cross-cultural learning and lost civilisations inform our understanding of wisdom and heritage. Through his investigations into archival structures, intellectual traditions and heritage preservation, Toni examines how the architecture of knowledge shapes societies, eras and human futures. Passionate about memory, culture and transmission, Toni focuses on how ideas are stored, shared and sustained — and how we might protect the legacy of human insight. His work highlights the intersection of education, history and preservation — guiding readers toward a deeper relationship with the knowledge that survives across time and borders. Blending archival science, anthropology and philosophy, Toni writes about the journey of knowledge — helping readers realise that what we inherit is not only what we know, but how we came to know it. His work is a tribute to: The libraries, archives and scholars that preserved human insight across centuries The cross-cultural flow of ideas that formed civilisations and worldviews The vision of knowledge as living, shared and enduring Whether you are a historian, educator or curious steward of ideas, Toni Santos invites you to explore the continuum of human wisdom — one archive, one idea, one legacy at a time.