The ancient Maya civilization left behind a treasure trove of knowledge encoded in elaborately illustrated manuscripts, yet most of these precious documents were lost to time and conquest.

🏛️ The Lost Libraries of Ancient Mesoamerica

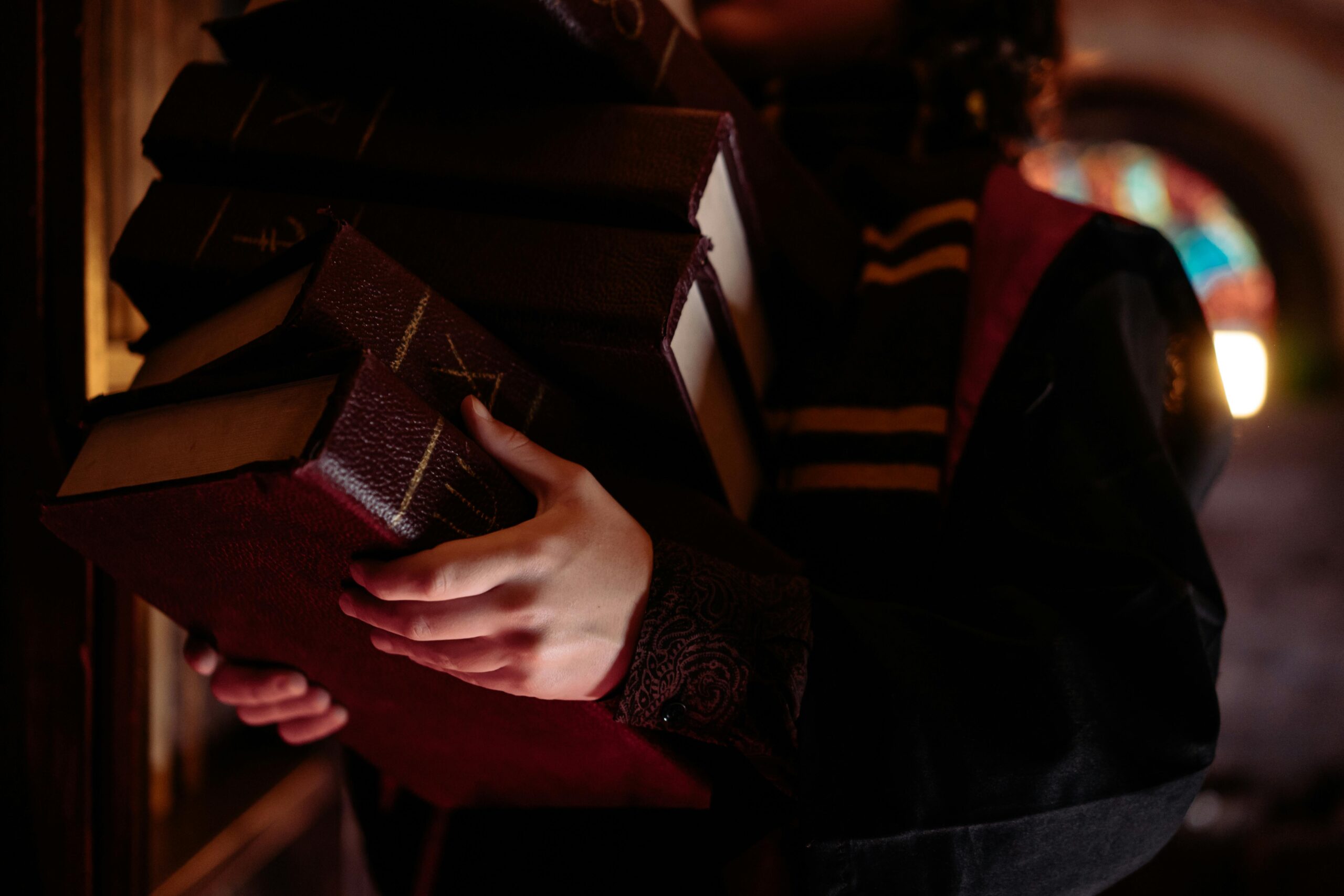

When Spanish conquistadors and missionaries arrived in the Americas during the 16th century, they encountered a sophisticated civilization with a complex writing system and extensive libraries. The Maya had developed one of the most advanced pre-Columbian cultures, complete with astronomical observations, mathematical achievements, and historical records meticulously documented in bark-paper books called codices.

Tragically, zealous missionaries viewed these manuscripts as works of the devil and systematically destroyed thousands of them. Diego de Landa, a Franciscan friar, famously ordered the burning of Maya codices in 1562 at Maní, Yucatán. In his own words, he stated they contained “nothing in which there was not to be seen superstition and lies of the devil.” This cultural catastrophe resulted in the near-total obliteration of Maya written heritage.

Today, only four complete Maya codices are known to have survived this systematic destruction, making them among the most precious artifacts in the world. These survivors—the Dresden, Madrid, Paris, and Grolier codices—represent merely a fraction of what was once an extensive corpus of Maya literature spanning history, astronomy, religion, agriculture, and medicine.

📜 The Four Surviving Treasures

Each of the surviving Maya codices has its own remarkable story of survival and rediscovery, offering unique insights into the ancient Maya worldview and scientific knowledge.

The Dresden Codex: A Masterpiece of Maya Astronomy

Considered the most elaborate and best preserved of the surviving codices, the Dresden Codex contains 39 leaves written on both sides, creating 78 pages of intricate glyphs and illustrations. Named after the city where it has been housed since the 1730s, this manuscript is primarily an astronomical and astrological almanac.

The Dresden Codex contains remarkably accurate tables for predicting solar eclipses, calculating the synodic period of Venus, and tracking the movements of Mars and other celestial bodies. The mathematical precision demonstrated in these calculations rivals contemporary European astronomical knowledge and showcases the Maya’s sophisticated understanding of celestial mechanics.

The Madrid Codex: Rituals and Daily Life

The Madrid Codex, also known as the Tro-Cortesianus Codex, is the longest surviving Maya manuscript with 56 leaves. It primarily focuses on horoscopes, almanacs for various rituals, and agricultural ceremonies. Unlike the Dresden Codex’s astronomical focus, the Madrid Codex provides invaluable insights into everyday Maya religious practices and seasonal ceremonies.

The manuscript depicts deities associated with different activities like hunting, beekeeping, weaving, and farming. These illustrations have proven instrumental in understanding Maya daily life, religious observances, and the integration of spiritual beliefs with practical activities.

The Paris Codex: Prophecies and Katun Cycles

The Paris Codex, discovered in a corner of the Paris National Library in 1859, consists of 11 surviving leaves. Though heavily damaged and partially deteriorated, this codex contains prophecies and rituals associated with the Maya calendar system, particularly the katun cycles—periods of approximately 20 years that were significant in Maya timekeeping.

The codex also includes representations of various Maya deities and ceremonies, providing additional context for understanding Maya religious cosmology and temporal philosophy.

The Grolier Codex: Controversial Authenticity

The Grolier Codex, discovered in a cave in Chiapas, Mexico, in the 1960s, has been the subject of intense scholarly debate regarding its authenticity. For decades, many experts questioned whether it was genuinely ancient or a modern forgery. However, recent scientific analysis has increasingly supported its authenticity, dating it to approximately 1230 CE.

This fragment contains only 10 surviving pages focused on the movements of Venus and associated ritual activities. If authentic—as now widely accepted—it represents the oldest known Maya codex and provides additional evidence of the Maya’s obsession with Venus cycles.

🔍 The Science Behind Codex Reconstruction

Reconstructing and interpreting Maya codices requires an interdisciplinary approach combining archaeology, linguistics, art history, astronomy, mathematics, chemistry, and increasingly, advanced digital technologies. The process presents numerous challenges due to the age of the manuscripts, their fragile condition, and the complexity of Maya hieroglyphic writing.

Decipherment of Maya Hieroglyphics

Maya script remained largely undeciphered until the mid-20th century, when scholars like Yuri Knorozov, Tatiana Proskouriakoff, and David Stuart made breakthrough discoveries. Unlike earlier assumptions that Maya glyphs were purely ideographic, researchers proved that the writing system combined logographic and syllabic elements.

This phonetic component meant that glyphs could be “read” rather than merely interpreted symbolically. Each glyph block typically contains a main sign accompanied by smaller affixes that modify pronunciation or meaning. Understanding this structure has allowed epigraphers to decode approximately 90% of Maya hieroglyphic texts.

Material Analysis and Conservation

The physical composition of Maya codices presents unique conservation challenges. The manuscripts were created on bark paper made from the inner bark of fig trees, covered with a lime coating that created a smooth writing surface. Pigments were derived from natural minerals and organic materials, creating vibrant colors that have remarkably endured centuries.

Modern conservation efforts employ non-invasive techniques including multispectral imaging, X-ray fluorescence, and radiocarbon dating to analyze the manuscripts without causing damage. These technologies reveal hidden details invisible to the naked eye, including erased texts, compositional underdrawings, and material degradation patterns.

Digital Reconstruction Technologies

Advanced imaging technologies have revolutionized codex research in recent decades. High-resolution multispectral photography captures images at various wavelengths beyond visible light, revealing faded pigments and obscured details. Ultraviolet and infrared imaging have uncovered previously illegible text and illustrated details lost to time.

Three-dimensional scanning creates precise digital models that researchers worldwide can examine without accessing the fragile originals. Machine learning algorithms now assist in glyph recognition, pattern identification, and even predictive reconstruction of damaged sections based on known Maya artistic and textual conventions.

🌟 Remarkable Discoveries Within the Codices

As decipherment progresses and new analytical techniques emerge, researchers continue making astonishing discoveries that reshape our understanding of Maya civilization.

Advanced Astronomical Knowledge

The codices reveal that Maya astronomers achieved remarkable precision in their celestial observations without telescopes or modern instruments. The Dresden Codex’s Venus tables predict the planet’s appearances as morning and evening star with an error of only two hours over 500 years—an extraordinary achievement.

Maya astronomers also calculated the lunar cycle with incredible accuracy, understanding eclipse prediction and creating correction formulas to account for the slight discrepancy between their 260-day sacred calendar and the actual solar year. This astronomical sophistication supported agricultural planning, ritual scheduling, and political legitimacy.

Mathematical Innovations

The codices demonstrate the Maya’s sophisticated mathematical system, including their independent invention of the concept of zero—a revolutionary innovation that preceded its adoption in Europe by centuries. The Maya used a vigesimal (base-20) number system rather than the decimal system familiar to modern readers.

Mathematical notation in the codices employs a simple yet elegant system using dots (representing one) and bars (representing five), combined with positional notation that allowed calculation of enormous numbers needed for astronomical and calendrical calculations spanning thousands of years.

Medical and Botanical Knowledge

Though less extensively preserved than astronomical content, the codices contain references to medicinal plants, healing rituals, and disease concepts. These passages suggest sophisticated ethnobotanical knowledge, with specific plants associated with particular ailments and deities governing different aspects of health and illness.

Cross-referencing codex information with ethnographic accounts from early colonial sources and modern Maya descendant communities has helped identify many of these plants and their traditional uses, some of which have proven pharmacologically significant.

🎨 The Art and Symbolism of Codex Illustrations

Maya codices are not merely text documents but elaborate works of art combining written language with sophisticated visual storytelling. The illustrations employ a distinctive artistic style with specific conventions for representing deities, humans, animals, and cosmological concepts.

Deity figures appear throughout the codices, each identifiable by specific attributes, colors, and associated glyphs. The rain god Chaac is depicted with reptilian features and carrying lightning bolts. The maize god appears youthful with an elongated head resembling a corn cob. These visual conventions created a standardized iconographic language instantly recognizable to educated Maya viewers.

Colors carried symbolic meanings beyond aesthetic considerations. Red often associated with east and life, black with west and death, white with north, and yellow with south. The use of specific pigments—including the famous Maya blue, a chemically stable color that has remarkably resisted fading—represents another aspect of Maya technological achievement.

🔬 Modern Research Methods and Collaborative Projects

Contemporary codex research increasingly emphasizes international collaboration and open access to digitized resources, democratizing access to these precious artifacts and accelerating the pace of discovery.

International Digitization Initiatives

Major institutions housing Maya codices have undertaken comprehensive digitization projects, creating high-resolution images freely available to researchers and the public worldwide. The Saxon State and University Library Dresden, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, and Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History have all made their codex holdings accessible online.

These digital resources enable scholars without travel funding to conduct research, facilitate comparative studies across codices, and preserve the documents’ current condition for future reference even if physical deterioration continues.

Community-Engaged Scholarship

Modern Maya communities, descendants of the codices’ creators, increasingly participate in research and interpretation efforts. Many contemporary Maya people maintain traditional knowledge systems, ritual practices, and languages that provide crucial context for understanding codex content.

This collaborative approach challenges earlier research paradigms that excluded indigenous perspectives, recognizing that Maya cultural heritage belongs to living communities, not merely academic institutions. Indigenous scholars and knowledge keepers offer interpretive insights that purely outsider perspectives might miss.

💡 What the Codices Tell Us About Maya Worldview

Beyond specific factual content, the codices reveal fundamental aspects of Maya philosophy, cosmology, and conceptual frameworks that structured their understanding of existence.

The Maya conceived of time as cyclical rather than linear, with historical events, astronomical phenomena, and ritual obligations repeating in predictable patterns across vast temporal scales. This cyclical time concept appears throughout the codices in recurring glyphic sequences and repeating iconographic patterns.

The integration of astronomy, agriculture, ritual, and governance in codex content demonstrates the Maya worldview’s holistic nature. Religious ceremony, agricultural practice, political authority, and scientific observation were not separate domains but interconnected aspects of a unified cosmological understanding.

🌍 The Ongoing Search for Lost Codices

Despite the survival of only four recognized complete codices, researchers remain hopeful that additional Maya manuscripts may yet be discovered. Archaeological investigations continue throughout the Maya region, and climate-controlled caves or sealed archaeological contexts might preserve previously unknown codices.

Several fragments and pages of uncertain provenance have surfaced over the years, though authentication remains challenging. The discovery of even a single additional page would represent an invaluable addition to our understanding of Maya civilization.

Beyond physical manuscripts, ongoing excavation of Maya sites reveals hieroglyphic inscriptions on monuments, pottery, and architecture that complement codex information. While not codices themselves, these inscriptions employ the same writing system and often reference similar astronomical, historical, and ritual themes.

🎓 Educational Impact and Public Engagement

Maya codices have captured public imagination, featuring in museum exhibitions, documentaries, and educational programs worldwide. This popular interest helps secure funding for continued research while raising awareness about indigenous American intellectual achievements often overlooked in conventional historical narratives.

Exhibitions of facsimiles—carefully created reproductions—allow public viewing without risking damage to originals. These facsimiles employ traditional materials and techniques when possible, providing insights into codex creation processes while making this cultural heritage accessible to broader audiences.

Educational programs increasingly incorporate codex studies into curricula about pre-Columbian civilizations, mathematical history, astronomical traditions, and indigenous knowledge systems. This integration challenges Eurocentric narratives and demonstrates that sophisticated scientific inquiry flourished in diverse cultural contexts.

🔮 Future Directions in Codex Research

As technology advances and research methodologies evolve, new possibilities emerge for understanding these ancient manuscripts. Artificial intelligence and machine learning applications show particular promise for accelerating glyph decipherment, identifying textual patterns, and even predicting missing content in damaged sections.

Computational analysis of writing styles may eventually distinguish individual scribes who created specific codex sections, revealing whether single authors or multiple collaborators produced these manuscripts. Such discoveries would illuminate Maya scholarly practices and knowledge transmission systems.

Continued interdisciplinary collaboration combining traditional scholarly methods with cutting-edge technology promises to unlock remaining mysteries within these precious survivors of Maya civilization. Each advance in understanding represents not merely academic achievement but also a form of justice—recovering knowledge deliberately destroyed and honoring the intellectual legacy of the codices’ creators.

The Maya codices stand as testament to human curiosity, scientific inquiry, and artistic achievement. These fragile bark-paper manuscripts survived conquest, colonization, and centuries of neglect to share their wisdom across time. Through careful reconstruction, patient decipherment, and respectful engagement with Maya descendant communities, researchers continue uncovering ancient mysteries—revelations that illuminate not only the Maya past but also universal human drives to understand our world, track time’s passage, and preserve knowledge for future generations. The fascinating world of Maya codex reconstruction remains an active, evolving field where each discovery adds another piece to this extraordinary puzzle of ancient American intellectual achievement.

Toni Santos is a knowledge-systems researcher and global-history writer exploring how ancient libraries, cross-cultural learning and lost civilisations inform our understanding of wisdom and heritage. Through his investigations into archival structures, intellectual traditions and heritage preservation, Toni examines how the architecture of knowledge shapes societies, eras and human futures. Passionate about memory, culture and transmission, Toni focuses on how ideas are stored, shared and sustained — and how we might protect the legacy of human insight. His work highlights the intersection of education, history and preservation — guiding readers toward a deeper relationship with the knowledge that survives across time and borders. Blending archival science, anthropology and philosophy, Toni writes about the journey of knowledge — helping readers realise that what we inherit is not only what we know, but how we came to know it. His work is a tribute to: The libraries, archives and scholars that preserved human insight across centuries The cross-cultural flow of ideas that formed civilisations and worldviews The vision of knowledge as living, shared and enduring Whether you are a historian, educator or curious steward of ideas, Toni Santos invites you to explore the continuum of human wisdom — one archive, one idea, one legacy at a time.