The ancient world holds a treasure trove of written knowledge that laid the groundwork for modern scientific inquiry and understanding.

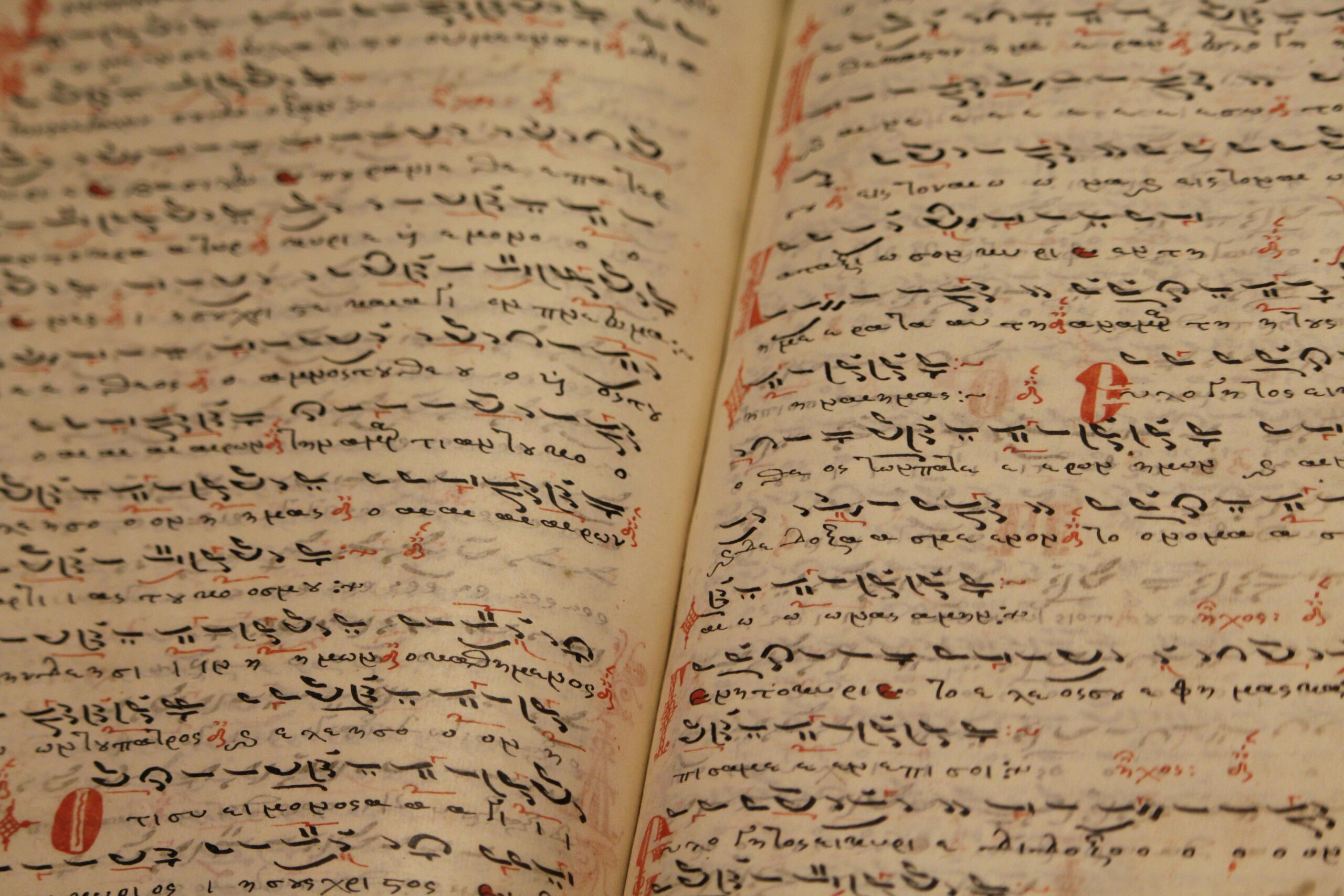

Long before the Scientific Revolution transformed our approach to understanding nature, ancient civilizations were meticulously recording observations, conducting experiments, and developing theories about the world around them. These proto-scientific texts represent humanity’s earliest attempts to systematically explain natural phenomena, medical conditions, astronomical events, and mathematical principles. From Babylonian astronomical tablets to Egyptian medical papyri, these ancient writings reveal sophisticated systems of thought that challenge our assumptions about the intellectual capabilities of our ancestors.

The term “proto-scientific” acknowledges that while these texts didn’t follow modern scientific methodology, they nonetheless represented systematic attempts to understand, predict, and control natural phenomena. They bridge the gap between mythology and science, showing how human curiosity and practical necessity drove the development of empirical observation and logical reasoning long before the formalization of scientific methods.

🏺 The Mesopotamian Legacy: Where Science Began

Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, produced some of humanity’s earliest proto-scientific texts. The Sumerians, Babylonians, and Assyrians left behind thousands of clay tablets containing mathematical calculations, astronomical observations, and medical prescriptions that demonstrate remarkable sophistication.

The Babylonian astronomical diaries, dating from the 8th century BCE onwards, represent one of the most systematic observation programs in ancient history. These cuneiform tablets recorded celestial events with impressive precision, including lunar eclipses, planetary positions, and meteorological phenomena. The Babylonians developed mathematical astronomy, creating algorithms to predict astronomical events without necessarily understanding the physical mechanisms behind them.

Their mathematical achievements were equally impressive. The Plimpton 322 tablet, dating to approximately 1800 BCE, contains what appears to be a sophisticated table of Pythagorean triples, suggesting advanced understanding of mathematical relationships centuries before Pythagoras himself. The sexagesimal (base-60) number system developed in Mesopotamia still influences our measurement of time and angles today.

Medical Knowledge Preserved in Clay

Mesopotamian medical texts reveal a complex system combining empirical observation with religious and magical elements. These texts classified diseases, described symptoms, and prescribed treatments that included both pharmacological remedies and ritual practices. While modern readers might dismiss the magical components, the empirical observations of symptoms and the practical effectiveness of many herbal remedies demonstrate genuine medical knowledge.

The diagnostic handbooks followed a consistent format: “If a patient exhibits [symptoms], he suffers from [disease] and should be treated with [remedy].” This if-then logical structure represents early systematic medical thinking, even if the underlying disease theory differed from modern understanding.

📜 Egyptian Papyri: Ancient Medical and Mathematical Wisdom

Ancient Egypt produced proto-scientific texts that continue to amaze scholars with their practical sophistication. Written primarily on papyrus, these texts covered medicine, mathematics, astronomy, and engineering, revealing a civilization deeply engaged with systematic knowledge.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus, dating to approximately 1600 BCE but likely copying earlier material, is considered the world’s oldest surgical document. Unlike many ancient medical texts, it maintains a remarkably rational, empirical approach. It describes 48 surgical cases, organized anatomically from head injuries downward, providing diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment recommendations with minimal magical elements.

What makes this papyrus particularly proto-scientific is its systematic organization, its use of case studies, and its honest assessment of which conditions could be treated successfully. For untreatable cases, the physician candidly states “an ailment not to be treated,” demonstrating intellectual honesty rare in ancient medical texts.

Egyptian Mathematical Innovation

The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus and the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus showcase Egyptian mathematical capabilities. These texts contain problems and solutions involving fractions, algebra, geometry, and practical calculations for construction, land measurement, and resource distribution. The problems often present real-world scenarios: dividing loaves among workers, calculating pyramid volumes, or determining field areas.

Egyptian mathematics was fundamentally practical, developed to solve concrete problems in administration, construction, and commerce. While lacking the abstract theoretical framework of later Greek mathematics, Egyptian mathematical texts demonstrate systematic problem-solving approaches and algorithmic thinking that qualify as proto-scientific.

🔬 Greek Natural Philosophy: The Birth of Theoretical Science

Ancient Greek thinkers transformed proto-scientific inquiry by introducing systematic theoretical frameworks and logical argumentation. While not conducting experiments in the modern sense, Greek natural philosophers developed comprehensive explanatory systems based on observation and rational deduction.

The Presocratic philosophers sought natural explanations for phenomena previously attributed solely to divine action. Thales proposed water as the fundamental substance, Anaximander theorized about infinite apeiron, and Democritus developed atomic theory. Though speculative, these theories represented attempts to find unifying principles underlying natural diversity.

Aristotle created the most comprehensive proto-scientific system in antiquity. His works on physics, biology, meteorology, and astronomy established frameworks that dominated Western thought for nearly two millennia. While modern science has superseded many of his specific conclusions, his systematic categorization, careful observation, and logical argumentation established methodological principles still valuable today.

Hippocratic Medicine: Rational Approaches to Health

The Hippocratic Corpus, attributed to Hippocrates and his followers, revolutionized medical thinking by emphasizing natural causes and treatments over supernatural explanations. These texts established medicine as a rational discipline based on observation, experience, and systematic theory.

The Hippocratic approach included detailed case histories, environmental factors affecting health, and the theory of humoral balance. While humoral theory proved incorrect, the emphasis on environmental influences, diet, and lifestyle in maintaining health resonates with modern preventive medicine. The famous Hippocratic Oath established ethical standards that continue influencing medical practice.

🌟 Ancient Astronomy: Mapping the Heavens

Astronomical texts from various ancient civilizations demonstrate humanity’s long fascination with celestial phenomena. These texts served practical purposes—creating calendars, predicting seasons, timing agricultural activities—while also addressing fundamental questions about cosmic order.

The Almagest by Ptolemy, compiled in the 2nd century CE, synthesized centuries of Greek and Babylonian astronomical knowledge. It presented a comprehensive geocentric model of the universe that could predict planetary positions with remarkable accuracy. While we now know the geocentric model is incorrect, the Almagest represents sophisticated mathematical astronomy and remained the standard astronomical text for over a thousand years.

Chinese astronomical texts, recorded continuously for millennia, documented celestial events including supernovae, comets, and planetary movements. The Chinese developed their own astronomical theories, created star catalogs, and built sophisticated instruments for observation. Their systematic record-keeping provided data that modern astronomers still use to study historical celestial events.

🌿 Ancient Pharmacology and Botany

Proto-scientific texts on medicinal plants reveal extensive empirical knowledge accumulated through generations of observation and experimentation. These works documented plant properties, preparation methods, and therapeutic applications, forming the foundation of pharmacology.

Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica, compiled in the 1st century CE, described approximately 600 medicinal plants along with their therapeutic uses. This comprehensive pharmacopeia remained influential for over 1,500 years. Modern analysis has confirmed the genuine therapeutic properties of many plants Dioscorides described, validating ancient empirical observation.

Similar botanical and pharmacological texts emerged in India (Ayurvedic texts), China (Shennong Ben Cao Jing), and the Arab world. These traditions developed independently but shared common features: systematic categorization, detailed descriptions, and practical therapeutic applications based on accumulated experience.

🔢 Mathematical Texts: The Language of Science

Mathematical texts from ancient civilizations reveal sophisticated numerical and geometric understanding. Mathematics served practical needs—commerce, taxation, construction, astronomy—while also developing as an intellectual discipline valued for its own sake.

Euclid’s Elements, compiled around 300 BCE, organized geometric knowledge into a systematic, axiom-based framework that established the model for mathematical reasoning. Its logical structure—defining terms, stating axioms, proving theorems—exemplifies the deductive method central to scientific thinking.

Ancient Indian mathematics made remarkable contributions, including the decimal place-value system, the concept of zero, and advanced trigonometry. These innovations, preserved in Sanskrit texts like the Sulba Sutras and later works by Aryabhata and Brahmagupta, transformed mathematics and enabled scientific advances worldwide.

⚗️ Alchemy: The Proto-Science of Transformation

Alchemical texts, though often dismissed as pseudoscience, represented serious proto-scientific inquiry into matter’s nature and transformation. Alchemists conducted systematic experiments, developed laboratory techniques, and accumulated practical knowledge about chemical substances and reactions.

The goals of alchemy—transmuting base metals to gold, creating the philosopher’s stone, discovering the elixir of life—may seem fantastical, but the experimental approach was genuinely proto-scientific. Alchemists carefully recorded procedures, observed reactions, and developed theories to explain their observations. Their work laid foundations for modern chemistry.

Texts like the Emerald Tablet and works by Jabir ibn Hayyan (Geber) combined practical chemical knowledge with philosophical speculation. They described distillation, crystallization, calcination, and other processes still used in chemistry. The allegorical language that makes alchemical texts difficult to interpret may have served to protect trade secrets while allowing initiates to understand practical procedures.

🌍 Preserving and Translating Ancient Knowledge

The survival of proto-scientific texts often depended on dedicated preservation and translation efforts across centuries and cultures. Many ancient works survived only because scholars valued them enough to copy, translate, and transmit them to subsequent generations.

During the Islamic Golden Age, scholars in Baghdad, Cairo, and Cordoba translated Greek, Persian, and Indian scientific texts into Arabic, preserving and expanding upon them. This translation movement saved works that might otherwise have been lost and facilitated knowledge exchange between civilizations.

Medieval European scholars later translated Arabic texts into Latin, reintroducing classical knowledge to Western Europe and helping spark the Renaissance and Scientific Revolution. Each transmission involved not just translation but interpretation, commentary, and integration with existing knowledge frameworks.

💡 The Modern Rediscovery and Study of Ancient Texts

Archaeological discoveries continue revealing proto-scientific texts that expand our understanding of ancient knowledge. The decipherment of ancient scripts—cuneiform, hieroglyphics, Linear B—has unlocked vast libraries of ancient learning previously inaccessible.

Modern scholars employ multidisciplinary approaches to understand these texts, combining linguistics, archaeology, history of science, and experimental reconstruction. They’re discovering that ancient peoples possessed more sophisticated scientific understanding than previously assumed.

Digital humanities projects are making ancient texts more accessible through online databases, digital editions, and computational analysis. These resources enable researchers worldwide to study proto-scientific texts, identify patterns, and trace the development of scientific concepts across cultures and centuries.

🔍 What Ancient Texts Teach Us Today

Studying proto-scientific texts offers more than historical interest; it provides valuable perspectives on the nature of scientific inquiry itself. These texts remind us that science emerged gradually from practical problem-solving, careful observation, and systematic thinking rather than appearing suddenly with the Scientific Revolution.

Ancient texts also challenge cultural biases about the origins of science. Scientific thinking emerged independently in multiple civilizations, each contributing unique insights and methodologies. Recognizing this diversity enriches our understanding of science as a human endeavor transcending cultural boundaries.

Furthermore, some ancient knowledge remains practically relevant. Traditional medical systems preserved in ancient texts contain genuine therapeutic insights. Ancient agricultural practices documented in proto-scientific texts offer sustainable alternatives to industrial methods. Ancient astronomical records provide data unavailable from modern observations alone.

🌐 The Continuum from Ancient Wisdom to Modern Science

Rather than viewing proto-scientific texts as primitive precursors to “real” science, we should recognize them as part of a continuous tradition of systematic inquiry. The questions ancient scholars asked—about matter’s nature, life’s origins, the universe’s structure—remain central to science today.

The transition from proto-science to modern science wasn’t a sudden break but a gradual refinement of methods, standards of evidence, and theoretical frameworks. Ancient scholars established foundations upon which later scientists built: systematic observation, logical reasoning, mathematical modeling, and the search for natural explanations.

Understanding this continuity fosters appreciation for science as an evolving human enterprise rather than a fixed body of knowledge. It reminds us that today’s scientific consensus, like ancient theories, represents our best current understanding subject to revision through continued inquiry.

The ancient writings explored in this article—from Mesopotamian tablets to Greek treatises, from Egyptian papyri to alchemical manuscripts—demonstrate humanity’s enduring quest to understand the natural world. These proto-scientific texts preserved and transmitted knowledge across generations, laying foundations for modern science. By studying them, we connect with thousands of years of human curiosity, ingenuity, and intellectual achievement, recognizing ourselves as inheritors of a magnificent tradition of systematic inquiry that continues evolving today. The ancient authors who carefully inscribed their observations and theories could not have imagined how their work would influence future millennia, yet their intellectual legacy remains vital, reminding us that the pursuit of knowledge transcends individual lives and connects humanity across time.

Toni Santos is a knowledge-systems researcher and global-history writer exploring how ancient libraries, cross-cultural learning and lost civilisations inform our understanding of wisdom and heritage. Through his investigations into archival structures, intellectual traditions and heritage preservation, Toni examines how the architecture of knowledge shapes societies, eras and human futures. Passionate about memory, culture and transmission, Toni focuses on how ideas are stored, shared and sustained — and how we might protect the legacy of human insight. His work highlights the intersection of education, history and preservation — guiding readers toward a deeper relationship with the knowledge that survives across time and borders. Blending archival science, anthropology and philosophy, Toni writes about the journey of knowledge — helping readers realise that what we inherit is not only what we know, but how we came to know it. His work is a tribute to: The libraries, archives and scholars that preserved human insight across centuries The cross-cultural flow of ideas that formed civilisations and worldviews The vision of knowledge as living, shared and enduring Whether you are a historian, educator or curious steward of ideas, Toni Santos invites you to explore the continuum of human wisdom — one archive, one idea, one legacy at a time.