Ancient scholars defied boundaries by mastering multiple languages, creating bridges between civilizations and preserving humanity’s collective wisdom across centuries.

🌍 The Dawn of Multilingual Knowledge Systems

Long before the digital age connected the world through instant translation, ancient scholars embarked on extraordinary intellectual journeys that required fluency in multiple languages. These remarkable individuals didn’t simply learn languages for communication—they became custodians of cross-cultural knowledge, translating texts that would otherwise have been lost to history and synthesizing ideas from disparate civilizations into coherent bodies of understanding.

The ancient world was a tapestry of linguistic diversity, with Greek, Latin, Arabic, Sanskrit, Chinese, Hebrew, and numerous other languages serving as vehicles for philosophy, science, medicine, and theology. Scholars who could navigate this linguistic landscape held the keys to entire libraries of human thought, and their multilingual capabilities made them invaluable to rulers, religious institutions, and academic centers throughout the ancient and medieval periods.

The Polyglot Pioneers of Alexandria

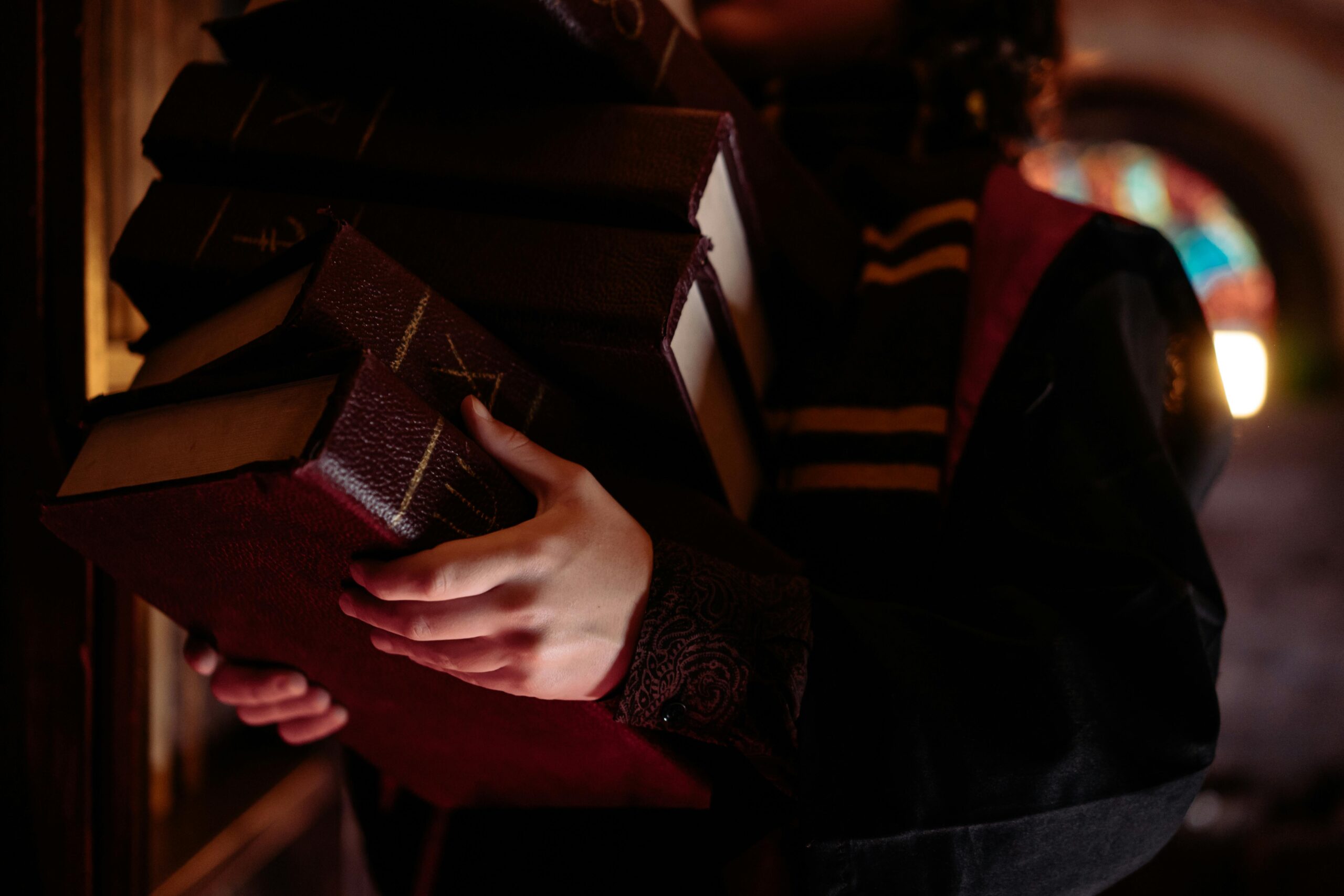

The Great Library of Alexandria stands as perhaps the most iconic symbol of ancient multilingual scholarship. This legendary institution, established in the 3rd century BCE, attracted scholars from across the known world. Here, texts in Egyptian hieroglyphics sat alongside Greek philosophical treatises, while Sanskrit astronomical works were studied next to Babylonian mathematical tablets.

Scholars at Alexandria didn’t merely collect these texts—they actively translated and commented upon them. The translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek, known as the Septuagint, exemplifies this collaborative multilingual effort. Legend tells of seventy-two Jewish scholars brought to Alexandria to create this translation, working independently yet producing remarkably consistent results—a testament to both linguistic skill and shared interpretive frameworks.

Breaking Down Language Barriers in Ancient Science

The scientific advances that emerged from Alexandria depended heavily on multilingual scholarship. Astronomers studying celestial movements needed access to Babylonian observational records, Egyptian calendrical systems, and Greek mathematical theories. Without scholars capable of reading and synthesizing these diverse sources, much of ancient astronomy would have remained fragmented and incomplete.

Euclid’s geometric principles, Ptolemy’s astronomical models, and Galen’s medical theories all benefited from this multilingual environment. These scholars drew upon knowledge recorded in multiple languages, creating syntheses that transcended any single cultural tradition.

📚 The Golden Age of Islamic Translation Movement

The Islamic Golden Age, spanning roughly from the 8th to the 14th centuries, witnessed perhaps the most ambitious multilingual scholarly project in human history. The House of Wisdom in Baghdad became the epicenter of a massive translation effort that brought Greek, Persian, Indian, and other texts into Arabic, preserving and expanding upon ancient knowledge while Europe languished in relative intellectual stagnation.

This wasn’t merely mechanical translation. Scholars like Hunayn ibn Ishaq mastered Greek, Syriac, Arabic, and Persian, enabling him to compare different manuscript traditions and produce translations of unprecedented accuracy. His approach to translating Galen’s medical works involved consulting multiple Greek manuscripts, correcting errors, and adding explanatory notes that demonstrated deep understanding of both the source material and the target language.

The Methodology Behind Medieval Translation

Islamic scholars developed sophisticated translation methodologies that balance literal accuracy with readability. They recognized that technical terminology required careful handling—sometimes Arabic lacked equivalent terms for Greek philosophical concepts, necessitating the creation of new vocabulary or the adaptation of existing words with expanded meanings.

This translation movement preserved works that would otherwise have been lost. Many Greek texts survive today only in Arabic translations, as the original manuscripts disappeared during various historical upheavals. The multilingual capabilities of Islamic scholars thus served as a lifeline connecting classical antiquity to the Renaissance.

The Multilingual Monasteries of Medieval Europe

While Islamic scholars translated eastward, European monasteries maintained their own multilingual traditions. Monks fluent in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and vernacular languages served as translators, copyists, and preservers of texts. The monastery libraries of Ireland, in particular, became renowned for their linguistic diversity, with Irish monks creating glossaries and annotations in multiple languages.

The translation schools of Toledo in the 12th and 13th centuries represented a crucial bridge between Islamic and Christian scholarship. Here, Christian, Jewish, and Muslim scholars collaborated on translations from Arabic into Latin, making the scientific and philosophical achievements of the Islamic world available to European readers. This collaborative environment required not just linguistic ability but also cultural sensitivity and mutual respect across religious boundaries.

Jerome and the Art of Sacred Translation

Saint Jerome’s translation of the Bible into Latin, known as the Vulgate, demonstrates the challenges and responsibilities of multilingual scholarship in religious contexts. Jerome learned Hebrew specifically to translate the Old Testament directly from the original rather than relying on Greek intermediaries. His letters reveal the painstaking care he took with terminology, the debates he engaged in with other scholars, and his awareness that translation choices could have theological implications.

Jerome’s work established principles that influenced translators for centuries: respect for the source text, awareness of audience needs, and recognition that some concepts resist direct translation. His multilingual approach—consulting Hebrew, Greek, and earlier Latin versions—created a translation that balanced scholarly rigor with liturgical utility.

🔍 Ancient China’s Linguistic Crossroads

The Silk Road created linguistic intersections where Chinese, Sanskrit, Persian, Turkic, and other languages mingled. Buddhist missionaries traveling from India to China faced extraordinary translation challenges, as Buddhist philosophical concepts developed in Sanskrit often lacked direct Chinese equivalents. Scholars like Kumarajiva and Xuanzang became legendary for their ability to convey not just words but entire conceptual frameworks across linguistic boundaries.

Xuanzang’s 7th-century journey to India exemplifies the dedication of ancient multilingual scholars. He spent years studying Sanskrit, returned with hundreds of texts, and devoted the remainder of his life to translation. His translations weren’t merely linguistic exercises—they required deep understanding of Buddhist philosophy, familiarity with multiple commentarial traditions, and sensitivity to how Chinese readers would receive these ideas.

The Challenge of Translating Religious Concepts

Translating Buddhist terms from Sanskrit to Chinese required remarkable creativity. Concepts like “dharma,” with its multiple meanings, or “nirvana,” describing a state beyond ordinary experience, demanded translators who were philosophers as much as linguists. Chinese translators developed various strategies: some transliterated Sanskrit terms, creating new Chinese words; others adapted existing Chinese philosophical vocabulary, accepting some semantic shift; still others created entirely new compounds that attempted to capture the original meaning.

The Polyglot Scholars of the Renaissance

The Renaissance revival of classical learning created new demands for multilingual scholarship. Humanists like Erasmus, who was fluent in Latin and Greek with knowledge of Hebrew, produced critical editions of ancient texts that compared multiple manuscripts and linguistic traditions. Their philological methods established standards for textual scholarship that remain influential today.

The printing press amplified the impact of multilingual scholarship. Polyglot Bibles, presenting parallel texts in Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Syriac, and Arabic, allowed scholars to compare linguistic traditions directly. The Complutensian Polyglot Bible, completed in 1517, represented years of collaborative work by scholars with different linguistic specializations, each contributing their expertise to this monumental project.

⚡ Methods and Challenges of Ancient Language Learning

How did ancient scholars actually acquire multiple languages? Unlike modern learners with structured courses and standardized tests, ancient polyglots developed their own learning methodologies based on available resources and personal circumstances.

Immersion played a crucial role. Scholars often traveled to regions where their target languages were spoken, spending years in foreign lands not just learning vocabulary and grammar but absorbing cultural contexts that gave languages their deeper meanings. This immersive approach, while time-consuming, produced scholars with genuine fluency rather than mere academic knowledge.

The Tools of Ancient Linguistic Study

Ancient scholars relied on several key resources for language acquisition:

- Bilingual texts: Works like the Rosetta Stone or bilingual manuscripts allowed scholars to compare known and unknown languages directly

- Grammatical treatises: Ancient grammarians produced systematic descriptions of their languages that foreign learners could study

- Glossaries and lexicons: Compiled lists of words with translations facilitated vocabulary building

- Personal tutors: Native speakers willing to teach their languages provided invaluable guidance

- Commentaries: Explanatory notes on difficult texts helped learners understand usage in context

Memory techniques were essential. Without modern recording devices or easily accessible reference materials, scholars developed mnemonic systems to retain vast amounts of linguistic information. Some created mental associations between languages, others composed verses encoding grammatical rules, and many simply engaged in continuous practice through reading, writing, and conversation.

🌟 The Impact on Knowledge Transmission

Multilingual scholarship served as the primary mechanism for knowledge transmission across cultural boundaries in the ancient world. Without these linguistic intermediaries, civilizations would have remained largely isolated, their achievements unknown beyond their linguistic communities. The global intellectual heritage we now take for granted exists largely because dedicated scholars bridged linguistic divides.

Consider mathematics: Greek geometry, Indian numerals, Chinese algorithms, and Islamic algebra combined to create the mathematical foundation of modern science. This synthesis required scholars who could access texts in multiple languages, recognize connections between different mathematical traditions, and communicate these insights across linguistic boundaries.

Preserving Knowledge Through Translation

Many ancient works survive only because multilingual scholars translated them. When libraries burned, manuscripts decayed, or civilizations collapsed, translations preserved knowledge that would otherwise have vanished. Greek philosophy survived the Dark Ages primarily in Arabic translation. Sanskrit astronomical texts influenced European science through multiple layers of translation. Chinese inventions spread westward through multilingual transmission chains.

This preservation function continues today. Scholars working with endangered languages race to document and translate texts before the last speakers disappear, recognizing that each lost language represents an irretrievable perspective on human experience and knowledge.

Lessons for Modern Language Learning

Ancient multilingual scholars offer valuable insights for contemporary language learners. Their approaches emphasized depth over speed, cultural understanding over mere vocabulary acquisition, and practical application through translation and commentary. They recognized that language learning is fundamentally connected to knowledge acquisition—learning a language meant accessing that language’s intellectual traditions.

Modern technology provides unprecedented resources for language learning, yet the fundamental challenges remain similar. Understanding cultural context, developing genuine fluency, and bridging conceptual frameworks across languages still require dedication, time, and intellectual humility. Ancient scholars remind us that meaningful multilingualism involves more than passing proficiency tests—it requires sustained engagement with languages as living systems of thought and expression.

💡 The Continuing Relevance of Multilingual Scholarship

Today’s globalized world faces many of the same challenges that confronted ancient multilingual scholars: how to facilitate communication across linguistic boundaries, preserve endangered knowledge traditions, and create syntheses from diverse intellectual sources. Digital humanities projects, machine translation, and collaborative online platforms represent modern attempts to solve these age-old problems.

Yet technology alone cannot replace the deep understanding that characterized ancient scholarship. Automated translation tools, however sophisticated, struggle with cultural nuances, philosophical concepts, and historical contexts that multilingual human scholars navigate with relative ease. The future of knowledge transmission will likely involve partnerships between technological tools and human expertise, combining computational power with cultural sensitivity.

Building Bridges Across Time and Language

The legacy of ancient multilingual scholarship extends beyond the specific texts translated or knowledge transmitted. These scholars demonstrated that intellectual collaboration across cultural and linguistic boundaries enriches all participants, that diversity of perspective strengthens understanding, and that the effort required to truly comprehend another language and culture yields rewards far exceeding the initial investment.

Their example challenges modern assumptions about efficiency and specialization. In an age of increasing specialization, where scholars often focus narrowly on particular subdisciplines, the ancient polyglot model offers an alternative vision: broad learning, interdisciplinary synthesis, and recognition that profound insights often emerge at the intersections of different knowledge traditions.

As we navigate our interconnected world, the secrets of ancient multilingual scholarship remain surprisingly relevant. The dedication these scholars showed to mastering multiple languages, their sophisticated translation methodologies, their recognition that language and knowledge are inseparable, and their commitment to preserving and transmitting wisdom across boundaries—all these principles continue to guide those who work to connect cultures, preserve heritage, and build mutual understanding through linguistic scholarship.

The journey through language and knowledge that ancient scholars embarked upon never truly ends. Each generation faces new linguistic challenges, discovers previously unknown texts, and must find ways to make ancient wisdom accessible to contemporary audiences. By understanding how our predecessors approached these challenges, we gain both practical insights and inspiration for our own efforts to unlock the secrets contained in the world’s diverse linguistic traditions. 📖

Toni Santos is a knowledge-systems researcher and global-history writer exploring how ancient libraries, cross-cultural learning and lost civilisations inform our understanding of wisdom and heritage. Through his investigations into archival structures, intellectual traditions and heritage preservation, Toni examines how the architecture of knowledge shapes societies, eras and human futures. Passionate about memory, culture and transmission, Toni focuses on how ideas are stored, shared and sustained — and how we might protect the legacy of human insight. His work highlights the intersection of education, history and preservation — guiding readers toward a deeper relationship with the knowledge that survives across time and borders. Blending archival science, anthropology and philosophy, Toni writes about the journey of knowledge — helping readers realise that what we inherit is not only what we know, but how we came to know it. His work is a tribute to: The libraries, archives and scholars that preserved human insight across centuries The cross-cultural flow of ideas that formed civilisations and worldviews The vision of knowledge as living, shared and enduring Whether you are a historian, educator or curious steward of ideas, Toni Santos invites you to explore the continuum of human wisdom — one archive, one idea, one legacy at a time.