Manuscript conservation stands as humanity’s bridge between past and present, safeguarding irreplaceable documents that tell our collective story through centuries of knowledge, art, and culture.

🌍 The Sacred Duty of Manuscript Preservation

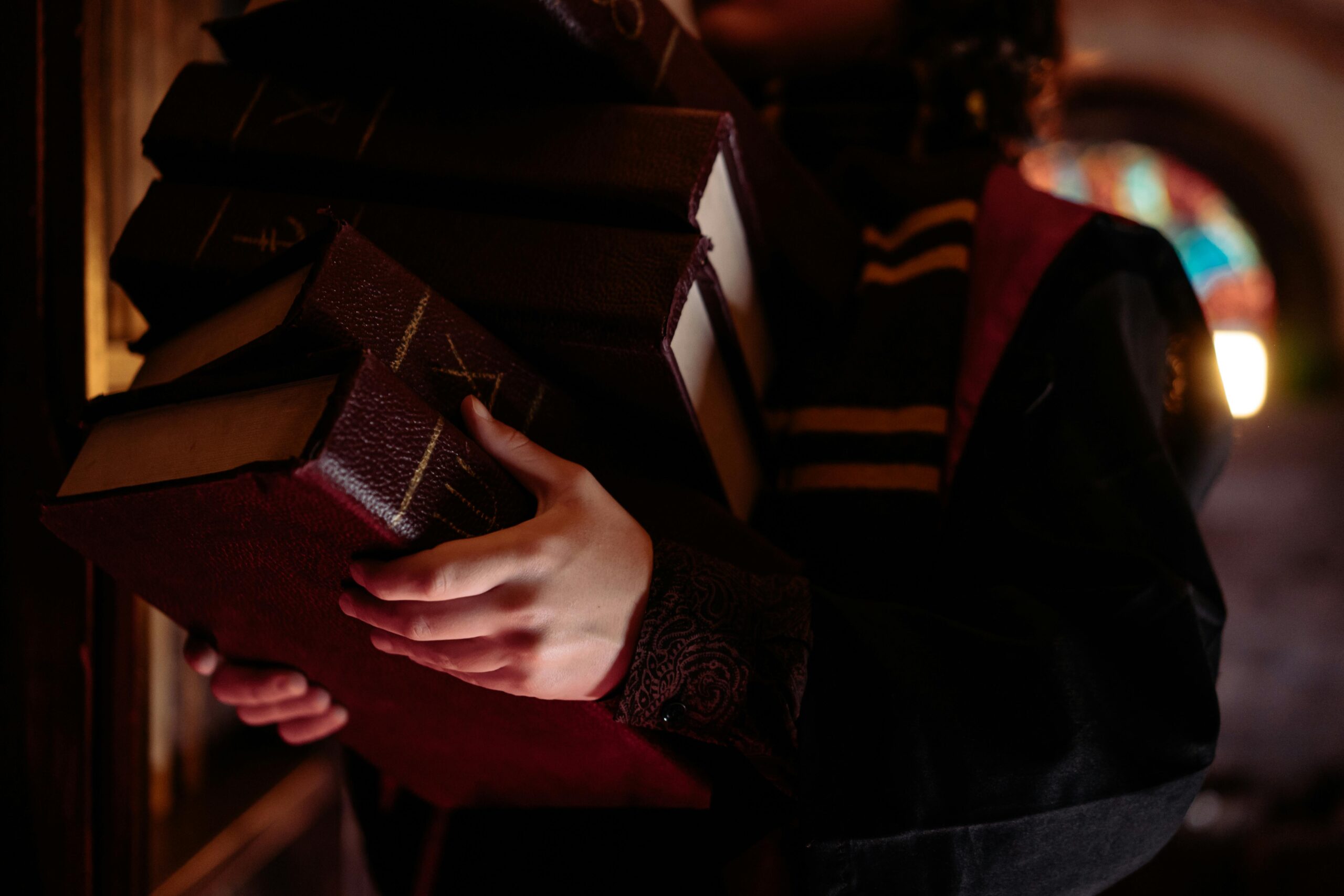

Every yellowed page, every faded ink stroke, every delicate fiber of ancient paper holds within it a fragment of human civilization. From illuminated medieval texts to ancient scrolls, historical manuscripts represent far more than mere documents—they are tangible connections to the minds, beliefs, and societies that shaped our world. The field of manuscript conservation has emerged as both science and art, requiring practitioners to master chemistry, history, craftsmanship, and cultural sensitivity in equal measure.

The urgency of this work cannot be overstated. Natural deterioration, environmental disasters, armed conflicts, and simple neglect threaten countless irreplaceable documents worldwide. Each manuscript lost represents knowledge that can never be recovered, stories that will never be told, and insights into human history that vanish forever. Conservation professionals work tirelessly against time itself, employing increasingly sophisticated techniques to arrest decay and restore readability to documents that might otherwise crumble into dust.

Understanding the Enemies of Historical Documents

Manuscripts face a relentless assault from multiple directions. Understanding these threats forms the foundation of effective conservation strategy, allowing professionals to prioritize interventions and develop comprehensive protection plans.

Environmental Degradation and Climate Challenges

Temperature fluctuations rank among the most destructive forces affecting manuscript preservation. Extreme heat accelerates chemical reactions within paper fibers, causing brittleness and discoloration, while cold can make materials contract and crack. Humidity presents an equally formidable challenge—too much moisture encourages mold growth and ink bleeding, while excessively dry conditions cause materials to become brittle and fragile.

Light exposure, particularly ultraviolet radiation, initiates photochemical degradation that fades inks and weakens paper structures. Many historical manuscripts have suffered irreversible damage from improper display conditions, with colors that once blazed brilliantly now reduced to pale shadows of their original intensity.

Biological Threats to Paper and Parchment

Living organisms pose significant dangers to manuscript collections. Insects such as silverfish, bookworms, and beetles view historical documents as nutritious meals, leaving behind destructive trails through irreplaceable texts. Rodents can devastate entire collections in remarkably short periods, shredding documents for nesting materials or simply gnawing through centuries-old bindings.

Microbiological threats include various mold and fungi species that thrive in damp conditions, producing enzymes that break down cellulose and collagen while staining materials with colored spores. Once established, mold infestations prove extremely difficult to eliminate without causing additional damage to delicate manuscripts.

🔬 Scientific Foundations of Modern Conservation

Contemporary manuscript conservation relies heavily on scientific understanding of material chemistry and degradation processes. This knowledge allows conservators to make informed decisions about treatment options and long-term storage solutions.

Material Analysis and Documentation

Before any intervention begins, conservators conduct thorough examinations using both traditional observation and advanced analytical techniques. Non-destructive testing methods such as multispectral imaging reveal hidden text, underlying drawings, and previous restoration attempts. X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy identifies pigments and inks without requiring physical samples, while fiber analysis determines the composition of paper or parchment substrates.

This investigative phase creates detailed documentation of each manuscript’s current condition, historical alterations, and structural weaknesses. Such records prove invaluable for tracking deterioration over time and evaluating the success of conservation interventions.

pH Levels and Chemical Stability

The acidity of paper directly correlates with its longevity. Many manuscripts produced after the mid-nineteenth century suffer from inherent acidity due to manufacturing processes that introduced sulfuric acid into paper production. This internal acidification causes self-destruction as the paper literally consumes itself through acid hydrolysis.

Conservation treatments often include deacidification processes that neutralize existing acids and introduce alkaline reserves to buffer against future acidification. Mass deacidification techniques can treat entire books without disbinding them, though severely degraded manuscripts may require individual leaf treatment.

Traditional Techniques Meet Modern Innovation

Manuscript conservation honors time-tested methods while embracing technological advances that enhance outcomes and expand possibilities for treatment.

The Gentle Art of Paper Repair

Skilled conservators practice techniques handed down through generations, including Japanese paper repair methods that use thin, long-fibered papers and wheat starch paste to mend tears and fill losses. These repairs must be both structurally sound and aesthetically sympathetic, supporting weakened areas without obscuring original content or introducing visually jarring elements.

Leaf casting represents a more mechanized approach to filling losses, using a suction table and pulp suspension to rebuild missing paper areas. The technique creates seamless repairs particularly valuable for extensive damage, though it requires considerable expertise to match the color, texture, and thickness of original materials.

Digital Technologies Revolutionizing Access and Preservation

High-resolution digital imaging has transformed manuscript conservation by creating detailed surrogates that allow researchers to study documents without handling fragile originals. Advanced imaging techniques capture information invisible to the naked eye, including erased text, hidden layers of composition, and deteriorated passages that standard photography cannot reveal.

Three-dimensional scanning documents entire codices, preserving not just content but also physical characteristics such as binding structure, page thickness variations, and evidence of use patterns. These digital twins serve as insurance against catastrophic loss while democratizing access to materials once available only to privileged scholars able to visit specific repositories.

📚 Regional Approaches to Manuscript Conservation

Different cultural traditions and climatic challenges have fostered diverse conservation philosophies and techniques across the globe.

European Traditions and Institutional Excellence

European conservation developed within institutions stewarding massive manuscript collections accumulated over centuries. The Vatican Library, British Library, and Bibliothèque nationale de France maintain world-class conservation laboratories employing specialists in parchment, paper, bindings, and illuminations. These institutions have pioneered many standardized conservation practices now adopted internationally.

European approaches traditionally emphasize reversibility—the principle that conservation treatments should be removable without damaging original materials, allowing future conservators to undo interventions as better techniques emerge. This philosophy reflects a humble recognition that current best practices may eventually be superseded by improved methodologies.

Middle Eastern and Islamic Manuscript Care

Islamic manuscript conservation addresses unique challenges presented by Arabic calligraphy, illumination styles, and binding structures distinct from European traditions. Many Islamic manuscripts feature water-soluble inks and pigments requiring specialized treatment protocols. Regional climate conditions, ranging from desert dryness to coastal humidity, demand conservation strategies tailored to local environmental realities.

Conservation centers in Cairo, Istanbul, Tehran, and elsewhere combine traditional knowledge preserved within families of artisan bookbinders with contemporary scientific approaches. This synthesis honors cultural heritage while applying modern understanding of material degradation and treatment options.

Asian Conservation Philosophies

East Asian manuscript conservation reflects philosophical perspectives that differ significantly from Western approaches. Japanese conservation, for instance, has long embraced complete renewal of deteriorated materials when necessary, viewing such interventions not as falsification but as acts of respect ensuring a document’s continued existence and functionality.

Chinese conservation traditions address unique formats including scrolls, albums, and accordion-style bindings constructed from materials ranging from silk to bamboo paper. These distinct physical forms require specialized expertise in mounting, remounting, and structural support that Western-trained conservators may lack without additional training.

⚡ Ethical Considerations in Conservation Practice

Manuscript conservation involves profound ethical responsibilities that extend beyond technical competence to questions of cultural ownership, historical authenticity, and access equity.

Balancing Preservation with Accessibility

Conservators face constant tension between protecting fragile materials and making them available for study and appreciation. Overly restrictive access policies preserve physical documents but may defeat the purpose of conservation by rendering materials functionally unavailable. Conversely, liberal handling policies risk accelerating deterioration through cumulative use damage.

Digital surrogates offer partial solutions, though they cannot fully replicate the experience of engaging with original materials. The texture of parchment, the dimensionality of illuminations, the physical evidence of historical use—these tangible qualities resist complete digital capture, making some level of physical access necessary for comprehensive scholarship.

Respecting Cultural Heritage and Ownership

Many manuscripts held in Western institutions originated from colonial-era acquisitions of questionable legitimacy. Contemporary conservation must acknowledge these complicated histories while navigating modern repatriation debates. Conservators may find themselves treating materials for return to source communities or training conservation professionals from those communities to care for repatriated materials.

Cultural sensitivity requires conservators to understand the spiritual, religious, or ceremonial significance certain manuscripts hold for specific communities. Treatment approaches must respect these meanings, consulting with cultural stakeholders about appropriate interventions and handling protocols.

🛡️ Disaster Preparedness and Emergency Response

Natural disasters, fires, floods, and armed conflicts pose catastrophic threats to manuscript collections. Effective preparedness minimizes losses when disasters strike, while trained emergency response maximizes salvage of affected materials.

Risk Assessment and Prevention

Comprehensive risk assessments identify vulnerabilities specific to each collection and location. Earthquake-prone regions require seismic-resistant shelving and storage solutions, while flood-risk areas necessitate elevated storage and waterproof barriers. Fire suppression systems must balance effectiveness against potential water damage to collections.

Disaster preparedness includes detailed response plans specifying priorities for salvage, emergency supply caches, and trained response teams familiar with safe handling and stabilization techniques. Regular drills ensure staff can execute emergency protocols efficiently under crisis conditions.

Post-Disaster Recovery Techniques

When disasters strike, immediate response proves critical. Water-damaged manuscripts require rapid freezing to arrest mold growth and prevent adhesion of wet pages. Specialized vacuum freeze-drying facilities can treat large quantities of water-damaged materials, though severely affected items may require individual treatment by skilled conservators.

Fire-damaged manuscripts present particularly challenging recovery scenarios, with heat-brittled materials requiring extreme delicacy in handling. Smoke and soot deposits must be removed without abrading fragile surfaces, while heat-altered inks may require advanced imaging techniques to recover illegible text.

Training the Next Generation of Conservators

Manuscript conservation requires years of intensive training combining academic study with hands-on apprenticeship. The field faces challenges ensuring sufficient numbers of skilled practitioners to meet global conservation needs.

Academic Programs and Professional Development

Leading conservation programs operate within institutions such as New York University, University College London, and the University of Texas at Austin. These programs balance scientific coursework in chemistry and materials science with practical training in treatment techniques and art historical study providing essential context for conservation decisions.

Professional development continues throughout conservators’ careers as new techniques emerge and understanding of material behavior deepens. International conferences, workshops, and publications facilitate knowledge exchange across borders and specializations.

Preserving Traditional Craft Knowledge

Many traditional conservation techniques risk disappearance as master practitioners retire without adequately trained successors. Organizations worldwide work to document traditional methods and connect younger conservators with experienced mentors. This knowledge transfer proves particularly urgent in regions where political instability, economic constraints, or limited institutional support threaten continuity of craft traditions.

🌟 Success Stories Worth Celebrating

Despite formidable challenges, conservation professionals achieve remarkable successes recovering seemingly lost manuscripts and preserving treasures for future generations.

The recovery of charred Herculaneum papyri demonstrates how advanced imaging can unlock texts previously considered unreadable. Multi-spectral imaging and X-ray phase-contrast tomography have revealed passages from these scrolls carbonized by Mount Vesuvius’s eruption in 79 CE, extracting information from manuscripts too fragile to physically unroll.

The Saint Catherine’s Monastery conservation project in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula exemplifies international collaboration preserving one of world’s oldest continuously operating libraries. Teams have treated thousands of manuscripts while training local staff to maintain collections independently, ensuring long-term preservation sustainability.

Looking Toward the Conservation Future

Emerging technologies and evolving methodologies promise enhanced capabilities for future conservation while presenting new challenges requiring thoughtful responses.

Artificial intelligence applications in manuscript conservation include automated damage detection, predictive deterioration modeling, and even algorithmic handwriting analysis assisting paleographic study. These tools may dramatically increase efficiency, allowing conservators to assess collection conditions more comprehensively and prioritize interventions more effectively.

Climate change presents perhaps the most significant long-term challenge to manuscript preservation. Rising temperatures, increased humidity, more frequent extreme weather events, and changing pest distributions will require adaptive conservation strategies. Institutions must invest in climate-controlled storage while developing emergency preparedness plans accounting for intensifying disaster risks.

Funding constraints perpetually challenge conservation programs, with preservation work often receiving lower priority than acquisitions or public programming. Advocacy efforts must communicate conservation’s essential role in maintaining cultural heritage, emphasizing that unpreserved collections inevitably deteriorate regardless of their historical significance or scholarly value.

The Irreplaceable Value of Original Manuscripts

In our increasingly digital age, some question whether physical manuscript preservation remains necessary when high-quality digital surrogates exist. This perspective fundamentally misunderstands what manuscripts represent and the information they contain beyond textual content.

Physical manuscripts embody their own histories through material evidence—marginalia revealing how readers engaged with texts, binding wear patterns indicating use frequency, repair histories documenting institutional priorities across centuries. These physical characteristics constitute historical evidence as valuable as the texts themselves, providing insights into book production, circulation patterns, and reading practices that purely textual analysis cannot access.

Conservation work honors the craftspeople who created these objects—scribes who spent years copying texts, illuminators who painted exquisite miniatures, binders who constructed durable structures. Allowing their works to deteriorate through neglect disrespects these artists’ skill and dedication while impoverishing human cultural heritage.

The collaborative, international nature of manuscript conservation demonstrates humanity’s better impulses—scholars and craftspeople transcending political boundaries to preserve shared cultural inheritance. In a fragmented world, this cooperative spirit offers hope that common values can unite diverse peoples in meaningful work benefiting all.

Manuscript conservation ultimately represents an act of faith in the future, a declaration that knowledge and beauty created centuries ago retain relevance and deserve transmission to generations yet unborn. Each preserved manuscript, each recovered text, each successfully treated binding affirms that history matters, that culture connects us across time, and that humanity’s creative achievements merit protection and celebration. The conservators pursuing this work serve as guardians not merely of objects but of memory itself, ensuring that voices from the past continue speaking to the present and future.

Toni Santos is a knowledge-systems researcher and global-history writer exploring how ancient libraries, cross-cultural learning and lost civilisations inform our understanding of wisdom and heritage. Through his investigations into archival structures, intellectual traditions and heritage preservation, Toni examines how the architecture of knowledge shapes societies, eras and human futures. Passionate about memory, culture and transmission, Toni focuses on how ideas are stored, shared and sustained — and how we might protect the legacy of human insight. His work highlights the intersection of education, history and preservation — guiding readers toward a deeper relationship with the knowledge that survives across time and borders. Blending archival science, anthropology and philosophy, Toni writes about the journey of knowledge — helping readers realise that what we inherit is not only what we know, but how we came to know it. His work is a tribute to: The libraries, archives and scholars that preserved human insight across centuries The cross-cultural flow of ideas that formed civilisations and worldviews The vision of knowledge as living, shared and enduring Whether you are a historian, educator or curious steward of ideas, Toni Santos invites you to explore the continuum of human wisdom — one archive, one idea, one legacy at a time.