The journey of cultural artifacts from their homelands to museums worldwide has shaped how civilizations understand their past, but repatriation efforts are now rewriting that narrative.

🏛️ Understanding the Global Movement for Cultural Repatriation

Cultural repatriation represents one of the most significant ethical debates in the modern museum world. As nations increasingly demand the return of artifacts removed during colonial periods, military conflicts, or through questionable acquisitions, institutions face difficult questions about ownership, cultural heritage, and historical justice. This movement transcends mere object transfer—it addresses centuries of imbalanced power dynamics and challenges the very foundations of encyclopedic museums.

The repatriation conversation has intensified dramatically over the past two decades. Countries like Greece, Egypt, Nigeria, and indigenous communities across the Americas and Oceania have become increasingly vocal about reclaiming their cultural patrimony. These efforts represent not just legal battles but profound statements about cultural identity, sovereignty, and the right of communities to connect with their ancestral heritage.

Major museums including the British Museum, the Louvre, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art now find themselves at the center of heated debates. While some institutions have begun voluntary repatriation programs, others maintain that their role as universal museums serves humanity’s collective interest. This tension between universalism and cultural nationalism defines the contemporary discourse around museum collections and colonial legacy.

The Historical Context: How Collections Were Assembled

Understanding the repatriation debate requires examining how Western museums acquired their collections. During the 18th and 19th centuries, European powers expanded globally, and cultural objects flowed steadily from colonized territories to metropolitan centers. Archaeological expeditions, military conquests, and unequal trade relationships facilitated the transfer of countless artifacts.

The methods of acquisition varied considerably. Some objects were purchased through legitimate transactions, though often under conditions of extreme power imbalance. Others were seized as war trophies, excavated without permission, or removed through coercion. The Benin Bronzes, looted by British forces in 1897, exemplify this problematic history. Similarly, the Parthenon Marbles, removed by Lord Elgin in the early 1800s, continue generating controversy regarding the circumstances of their acquisition.

Colonial-era laws often legitimized these removals, but those legal frameworks were created by colonizing powers without input from local populations. This historical context complicates current ownership claims, as institutions cite centuries-old documents while source communities point to the inherently unjust conditions under which those documents were created.

🌍 Cultural Identity and the Psychology of Loss

The absence of cultural artifacts from their place of origin creates profound psychological and social impacts on communities. These objects often carry spiritual significance, embody ancestral connections, and serve as tangible links to historical narratives. When removed, they leave cultural voids that affect how communities understand themselves and transmit knowledge across generations.

For indigenous peoples particularly, the repatriation of sacred objects and ancestral remains holds deep significance. Many items housed in museums were never meant for public display—they served ceremonial purposes or were burial goods intended to accompany the deceased. Their exhibition violates cultural protocols and religious beliefs, causing ongoing harm to descendant communities.

The return of artifacts enables communities to reconnect with practices, languages, and traditions that colonialism sought to erase. When the Wampanoag people of Massachusetts successfully repatriated wampum belts and other items, they could reinvigorate traditional knowledge systems that had been disrupted. These objects become teaching tools, helping younger generations understand their heritage in ways that photographs or replicas cannot replicate.

Economic and Educational Considerations in Repatriation Debates

Museums often justify retention of contested artifacts by citing their role in education and scholarship. They argue that major institutions provide optimal conservation conditions, scholarly access, and public engagement opportunities that might not exist elsewhere. This perspective assumes that Western institutions are inherently better equipped to care for global heritage—an assumption many now challenge as paternalistic and outdated.

The economic dimensions of repatriation are complex. Major museums generate substantial tourism revenue, and iconic objects often serve as primary attractions. The British Museum, for instance, receives millions of visitors annually, many drawn by famous pieces like the Rosetta Stone or Parthenon Marbles. Institutions fear that repatriation could diminish their cultural capital and financial sustainability.

However, this economic argument overlooks the tourism and cultural benefits that repatriation could bring to source countries. The return of artifacts can catalyze museum development, cultural tourism, and educational programming in communities of origin. Nigeria’s plans for a new museum to house returning Benin Bronzes illustrates how repatriation can stimulate cultural infrastructure investment and create new opportunities for local communities.

Legal Frameworks and International Agreements 📜

The legal landscape governing cultural property and repatriation involves multiple international conventions and national laws. The 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property established important principles, but its non-retroactive nature limits its application to historical collections.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), enacted in 1990 in the United States, provides a model for legally mandated repatriation. This legislation requires federal institutions and museums receiving federal funding to inventory their collections of Native American human remains and cultural items, consult with tribes, and repatriate items upon request when cultural affiliation can be established.

European countries are beginning to develop their own frameworks. France passed legislation enabling repatriation of objects to Benin and Senegal, while the Netherlands established protocols for returning colonial-era objects. Germany has initiated dialogues regarding items from former colonies, particularly focusing on human remains and sacred objects. These developments signal a gradual shift in how institutions and governments approach historical collections.

Case Studies: Successful Repatriation Stories

Several high-profile repatriations demonstrate the diverse approaches and outcomes in this field. In 2021, the Smithsonian Institution returned 39 Benin Bronzes to Nigeria, acknowledging they were looted during the 1897 British military expedition. This decision reflected changing institutional attitudes and responded to decades of advocacy by Nigerian officials and cultural leaders.

Australia has been particularly active in repatriating indigenous ancestral remains. Over several decades, Australian museums have returned thousands of remains to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, enabling proper reburial according to cultural protocols. These repatriations have facilitated healing and reconciliation processes between indigenous communities and national institutions.

The return of Machu Picchu artifacts from Yale University to Peru in 2011 concluded a lengthy dispute. Yale excavated thousands of objects in the early 20th century, and Peru spent years seeking their return. The eventual agreement included provisions for traveling exhibitions and collaborative research, demonstrating how repatriation can incorporate partnership elements rather than complete severance.

🎭 The Cultural Renaissance Following Returns

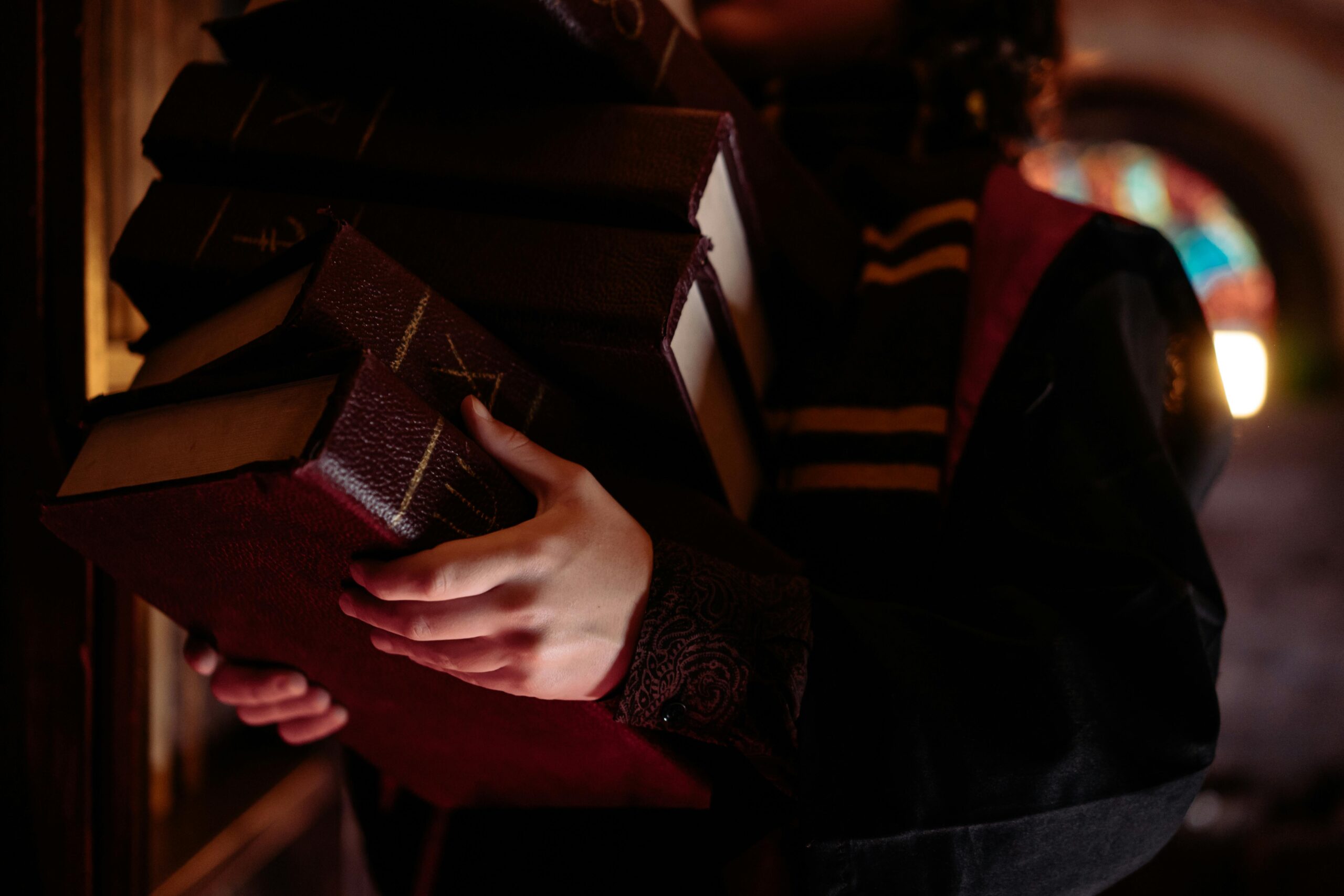

Repatriation often catalyzes cultural revitalization in recipient communities. When objects return, they bring not just historical artifacts but renewed opportunities for cultural practice, artistic inspiration, and community cohesion. Artists and craftspeople study returned objects to understand traditional techniques, designs, and materials that colonial disruption had obscured.

In New Zealand, the repatriation of Māori ancestral remains (kōiwi tangata) and sacred objects (taonga) has strengthened cultural identity and informed contemporary Māori art and activism. The Te Papa Tongarewa museum’s repatriation program has facilitated the return of remains from international institutions, enabling communities to conduct proper ceremonies and restore ancestral dignity.

These returns also stimulate scholarly production within source communities. Rather than being solely objects of Western academic study, repatriated artifacts become resources for indigenous scholarship, traditional knowledge systems, and community-led research. This shift democratizes knowledge production and challenges the historical monopoly Western institutions held over interpreting these objects.

Challenges and Complications in the Repatriation Process

Despite growing momentum, repatriation faces numerous practical and philosophical challenges. Establishing provenance for objects acquired centuries ago can be extraordinarily difficult when documentation is incomplete or absent. Questions arise about which contemporary entity represents the appropriate recipient when historical political structures have changed dramatically.

Some artifacts originated in regions that now encompass multiple modern nations, creating competing claims. Others come from cultures that no longer have direct descendants or have been absorbed into larger political entities. These situations require careful negotiation and sometimes creative solutions that prioritize cultural context over strict nationalist frameworks.

Conservation concerns present another challenge. While the assumption that Western museums provide superior care is increasingly questioned, legitimate concerns exist about ensuring appropriate conditions for sensitive materials. Collaborative conservation training, equipment sharing, and ongoing partnership between repatriating and receiving institutions can address these concerns while respecting sovereignty and ownership rights.

🌟 Digital Technology and Virtual Repatriation

Technological advances offer complementary approaches to physical repatriation. High-resolution 3D scanning, virtual reality, and comprehensive digital databases enable communities to access detailed representations of objects even when physical return isn’t immediately possible. While digital access cannot replace the cultural and spiritual significance of physical objects, it provides interim solutions and expands access.

Projects like the Digital Benin initiative create comprehensive online records of Benin Bronzes scattered across global collections. This documentation enables Nigerian scholars, artists, and communities to study their heritage regardless of where objects physically reside. Such projects also build the case for physical repatriation by making the extent of dispersed collections visible.

Virtual repatriation also addresses situations where physical return may be impractical—such as extremely fragile objects or those with shared cultural significance across multiple communities. Digital sharing allows simultaneous access without the exclusivity that physical possession entails, potentially offering models for complex cases where multiple communities have legitimate interests.

The Future of Museum Collections and Cultural Exchange

As repatriation reshapes museum landscapes, institutions are rethinking their missions and collection strategies. The concept of encyclopedic museums that represent all world cultures is giving way to more nuanced approaches emphasizing partnership, loans, and collaborative curation rather than permanent possession of others’ heritage.

Long-term loans offer one alternative model, allowing objects to be displayed internationally while acknowledging source community ownership. These arrangements can include provisions for periodic return for cultural ceremonies, collaborative exhibition development, and shared decision-making about conservation and interpretation. Such frameworks recognize that cultural exchange and preservation need not require permanent alienation from communities of origin.

Museums are also examining their contemporary collecting practices to ensure ethical acquisition. Enhanced due diligence, provenance research, and consultation with source communities before acquiring objects help prevent future controversies. These practices reflect lessons learned from repatriation debates and represent attempts to build more equitable relationships with global communities.

Building Bridges Through Respectful Dialogue 🤝

The most successful repatriation processes involve genuine dialogue between institutions and communities. Rather than adversarial legal battles, many cases now proceed through negotiation that acknowledges historical wrongs while seeking mutually beneficial outcomes. These conversations require museums to relinquish some authority and recognize communities as equal partners in determining their heritage’s future.

Training museum professionals in cultural competency, colonial history, and indigenous perspectives strengthens these dialogues. When curators and directors understand the depth of cultural significance these objects hold, they approach repatriation requests with greater empathy and flexibility. Similarly, involving community members in museum governance and decision-making processes ensures diverse perspectives shape institutional policies.

Educational programming that honestly addresses colonial histories and collection practices helps public audiences understand repatriation’s importance. Museums can serve as sites for confronting difficult histories rather than merely celebrating cultural achievements. This transparency builds trust and positions institutions as partners in addressing historical injustices rather than defenders of problematic legacies.

Repatriation as Justice and Reconciliation

Ultimately, repatriation represents a form of restorative justice. While returned objects cannot undo colonial violence or cultural suppression, they acknowledge wrongdoing and provide tangible restitution. For many communities, repatriation forms part of broader reconciliation processes addressing ongoing impacts of colonialism, including cultural disconnection, language loss, and intergenerational trauma.

The symbolic power of repatriation extends beyond individual objects. When institutions return artifacts, they validate source communities’ claims to their own history and affirm their authority over cultural interpretation. This validation counteracts centuries of Western narratives that positioned colonized peoples as passive subjects of history rather than active agents in their own stories.

As repatriation efforts expand, they create precedents and momentum for addressing other forms of historical injustice. The principles underlying cultural repatriation—acknowledging wrong acquisition, respecting cultural significance, and empowering communities—apply to broader questions of colonial legacy, land rights, and self-determination. Cultural repatriation thus becomes part of larger movements toward global justice and equity.

The cultural impact of repatriating lost artifacts extends far beyond museum walls. It touches fundamental questions about identity, justice, and how societies reckon with difficult histories. As more objects return to their communities of origin, they carry possibilities for healing, cultural renaissance, and more equitable relationships between nations and institutions. The journey of reclaiming history continues, reshaping our understanding of whose stories matter and who has authority to tell them.

Toni Santos is a knowledge-systems researcher and global-history writer exploring how ancient libraries, cross-cultural learning and lost civilisations inform our understanding of wisdom and heritage. Through his investigations into archival structures, intellectual traditions and heritage preservation, Toni examines how the architecture of knowledge shapes societies, eras and human futures. Passionate about memory, culture and transmission, Toni focuses on how ideas are stored, shared and sustained — and how we might protect the legacy of human insight. His work highlights the intersection of education, history and preservation — guiding readers toward a deeper relationship with the knowledge that survives across time and borders. Blending archival science, anthropology and philosophy, Toni writes about the journey of knowledge — helping readers realise that what we inherit is not only what we know, but how we came to know it. His work is a tribute to: The libraries, archives and scholars that preserved human insight across centuries The cross-cultural flow of ideas that formed civilisations and worldviews The vision of knowledge as living, shared and enduring Whether you are a historian, educator or curious steward of ideas, Toni Santos invites you to explore the continuum of human wisdom — one archive, one idea, one legacy at a time.